Pack Rats

Contact

University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture

Cooperative Extension Service

2301 S. University Ave.

Little Rock, AR 72204

Pack Rats

Moving, and by necessity and desire, downsizing is stressful. After a month of stirring my stuff, I finally called in professional help. It has helped because it is far easier for someone else to stuff your mementos into a trash bag than do it yourself. Looking at the piles of stuff, one can’t help but think of packrats.

While there are eight packrat species native to North America, they should not be confused with the Norway rat that is the scourge of mankind wherever they occur. By contrast, packrats — or, as they are called in the eastern states, woodrats — are sleek, clean animals that live happily in wild places away from human habitation. But, if something sits empty and unused long enough near a woodland where these animals live, a bit of cross-species interaction can be expected.

The gray colored woodrat male is about the size of a small squirrel but with the characteristic slender tail and large, bright shiny eyes, well adapted for its nighttime prowls. Females are slightly smaller. They feed on seeds, berries, vegetation, young twigs and bark — about anything in their environment. Their nests — called middens — are most often seen in sheltered bluff overhangs, in and around abandoned buildings and in the crotches of trees.

The middens look like a random pile of sticks but in fact are intricately woven structures that will be added to over many generations. Like beaver lodges, they have rooms where winter food supplies are cached, living quarters and multiple escape routes. And they are often decorated with bright and shiny things.

Packrats get their name for their characteristic habit of trading up. If they are heading back to their nest with an acorn to add to the pile, they are easily distracted by some new, shiny thing. Dropping the acorn, they carry off the new treasure. To the packrat this is a fair exchange, but for the new bride who left her wedding ring overnight on a picnic table only to find an acorn in its place in the morning, it smacks as a one-sided bargain.

We humans are also attracted to bright and shiny things. And sometimes, just things. On my office shelf, I rediscovered a fist sized piece of driftwood I fished out of the Chesapeake Bay more than 50 years ago. It was a short pine branch with a fusiform rust growth that reminded me of a dressed quail carcass ready for the frying pan. For some reason it has survived numerous moves and, for no good reason, now sits in my new home. Crazy, yes, I know.

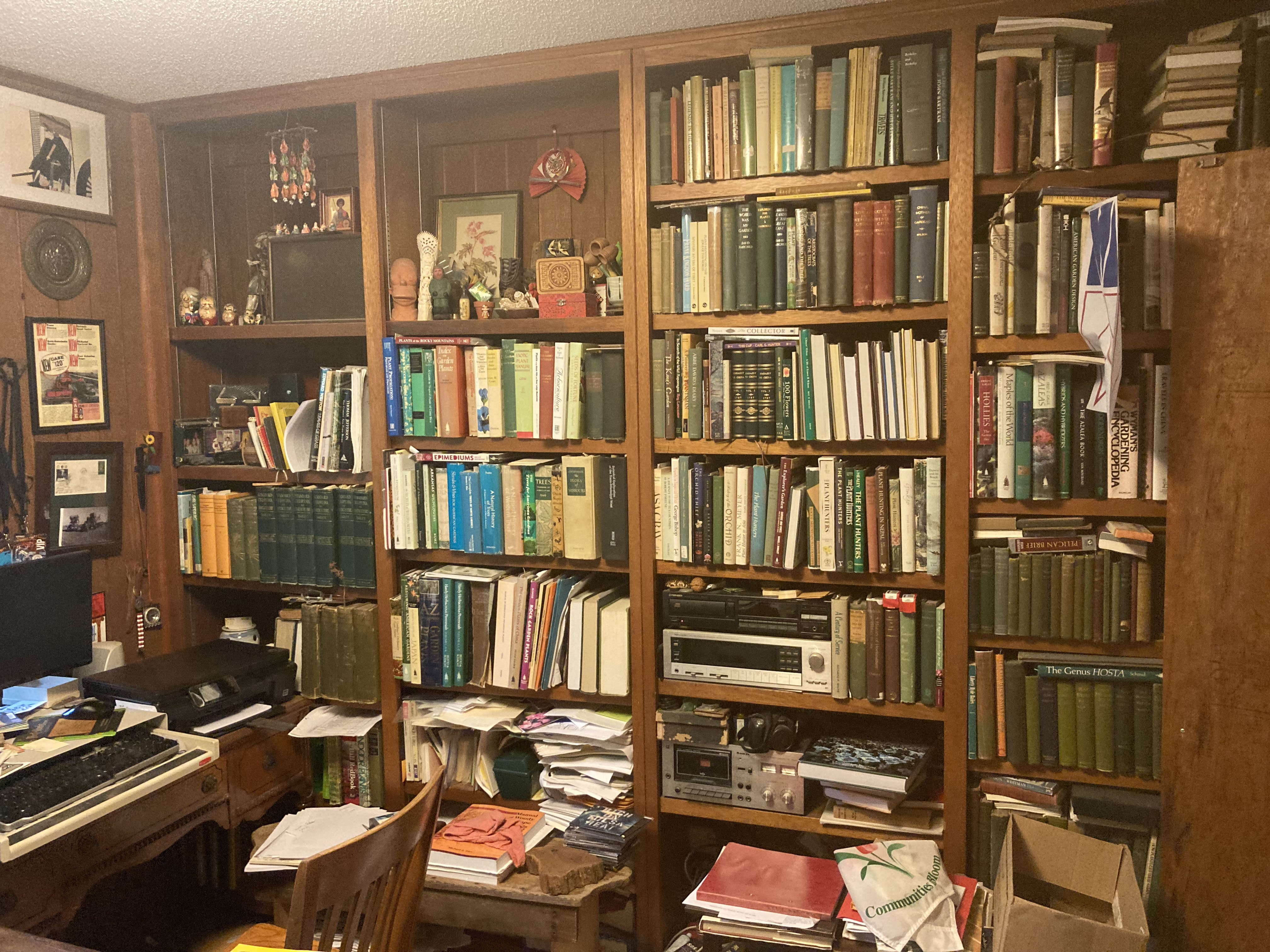

While this little memento is quirky (or so I think instead of crazy), books were my real problem. I’ve always loved to read and have surrounded myself with all kinds of books. Thousands of them. Maybe they were a way to make me feel smarter or more entitled to be called a college professor. But for whatever reason, they made me happy and I loved them.

The difference between hoarding and clutter is a bit subjective. Because my books were mostly lined up neatly on book shelves and I could usually find a volume I was searching for, I self-diagnose my condition as cluttered, not pathological hoarding. With more than 30 years in my work office at the university and another 30 in my home, stuff accumulates.

Now that I’m downsizing, I vow to do better. I only moved a hundred volumes or so and found acceptable homes for the most important subsets of my library, so the books are under control. From here on out I hope to live a curated life, saving only things of great significance. Birthday cards, no matter how cute or heartwarming the sentiment, go to the trash bin.

As Thoreau said in Walden, “I had three pieces of limestone on my desk, but I was terrified to find that they required to be dusted daily, when the furniture of my mind was all undusted still, and threw them out the window in disgust.” It has been a journey, and except for the five-gallon buckets of rocks I brought with me, I’m doing better. But I think I now grasp the idea that less is more, no matter how bright and shiny the thing may be, when it comes to stuff.