Glades

Contact

University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture

Cooperative Extension Service

2301 S. University Ave.

Little Rock, AR 72204

Glades

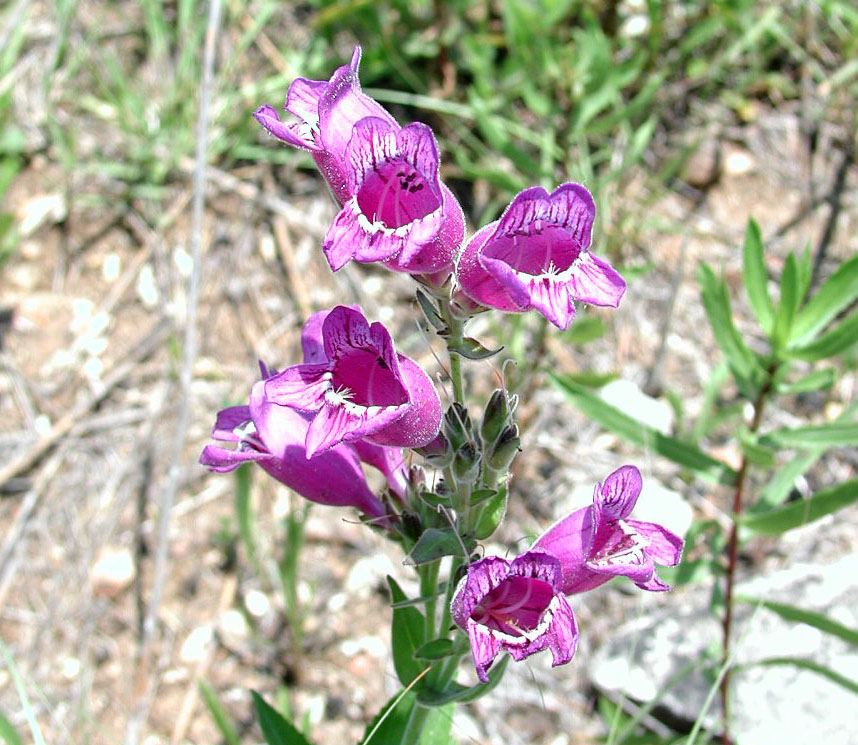

Last week a friend and I spied a small stand of the white flowered showy beardtongue (Penstemon cobaea) on our way to check out the baby buffalos at the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve north of Pawhuska, Oklahoma. This prompted me to seek out the rare purple-flowered form which is mostly scattered in limestone glades in the central Ozarks. This, in turn, got me to thinking about glades.

Ozark glades – sometimes referred to as balds – have been described as sunlit islands in a sea of trees. They exist because the rocky core of the Ozark dome is shallow, or sometimes completely exposed, on the flat surface of the land. There are two types of glades; limestone glades and sandstone glades. If there is soil it is shallow and very droughty. In situations where the rock surface is completely exposed, trees only gain a foothold by growing in cracks between the rocks. Sometimes water seeps across the surface of the stone during the spring rainy period. Plants grow in this scrim of water and organic matter, only to die quickly after a few days without rain.

I’ve only seen purple showy beardtongue in two places in Arkansas. I’ve spotted it several times on my way to Mountain Home where it grows on the dry, south facing limestone glades of the Springfield plateau. The other occurrence was in southern Arkansas where it grows in rows across pastures that had, until fairly recently by geological standards, been a part of the southern gulf coast where deposits of mussel and clam shells accumulated along old beaches. To thrive, this plant obviously needs alkaline soils, sun and excellent drainage.

Looking at the distribution map for this purple flowered beauty, I decided to search the limestone cliffs and glades west of Eureka Springs in Carroll County. My first stop was along Arkansas 187 that leads from the small town of Beaver to U.S. 62. Near this intersection is a limestone glade community that has been completely taken over by the Ashe Juniper (Juniperus ashei). At first glance this species looks like the overly abundant eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), but the needles are a bit more tufted and not as sharp pointed. And, if the tree is cut you will discover this predominantly central Texas species has white heartwood, not red as seen in our typical cedar.

Looking at the distribution map of the Ashe juniper in the Ozarks, you discover an eyebrow-shaped pattern that follow the White River as it moves north into Missouri and then heads back south towards Batesville when the river reenters Arkansas. It only grows on highly alkaline soils, but once established, every seed germinates and an impenetrable thicket soon develops. No doubt this once species-rich limestone glade was important in supporting the biodiversity of this part of the Ozarks, but today it is overrun with thick stands of 20-foot-tall trees. The roadway is kept clear of trees but I only found Penstemon arkansanum, the white flowered, limestone loving beardtongue that blooms about three weeks earlier than our more common penstemon species. Near this site I found a glade with a good assortment of limestone glade plants that was being kept open by the power company, but still no purple showy beardtongue.

On Sunday I had the opportunity to explore a sandstone glade that was being reclaimed from the forest. Before settlement, glades were mostly kept open by periodic fires that swept through the forest. Oaks primarily occupied the benches and river valleys, cedars escaped fires by perching on rocky outcrops, and glades existed on hilltops. When the fires stopped, eastern red cedars could grow in these droughty sites and began growing as “cedar glades” that crowded out everything else.

The reclamation effort was simple and straight forward. Remove the cedars, burn the glade area and, if the stock of native plants is too depauperate, reseed with native glade plants. And, of course, repeat as needed to keep the glade open. The mix of glade plants found on sandstone is very different than those found on limestone. I was delighted to discover opuntia cacti, widow’s cross sedum, fame flower (Talinum), a host of lichens and mosses, and other interesting little plants.