Kelly Loftin

Extension Entomologist

Controlling Horn Flies on Cattle

Fast Facts

- The horn fly spends most of its time on the back, head and shoulders of its host,

but during very hot or rainy weather, horn flies may move to the belly.

- When average horn fly counts approach the economic threshold (150-200/head for beef

cattle and 75-100 for dairy cattle), control should be considered.

- Effective horn fly management can result in a 15-30 pound increase in weight in stocker

calves during the growing season.

- The horn fly is primarily a pest of cattle and requires cattle dung for development, but it will occasionally feed on other mammals such as horses, sheep, goats and dogs.

A horn fly (Haematobia irritans) is about half the size of a house fly (Fig. 1) and spends most of its time on the

back, head and shoulders of its host (Fig. 2). They also feed on the belly and legs.

Figure 1. Horn fly feeding on a cow. (Image courtesy of Craig Sheppard, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org)

Figure 2. Horn flies on the back, neck and shoulders of a bull.

In addition to being smaller than the house fly, horn flies can be differentiated by piercing mouthparts that resemble a beak. Horn flies briefly leave the animal to deposit eggs on fresh cattle manure (less than 10 minutes old).

Both sexes feed on cattle and take 20 to 40 blood meals per day. Although rare, populations of up to 10,000 per animal have been documented. Development from egg to adult requires as little as 9-12 days, writes Dr Loftin. Larva hatch and develop within the manure (Fig. 3).

Mature larvae migrate to the lower portion of the manure pat or in the soil to pupate. Adults immerge from pupa after about 5 or 6 days. Horn flies survive the winter as pupae in the soil.

After the adult emerges, it seeks a host to begin blood feeding. An adult female may

begin laying eggs three days after emergence and may lay up to 400 eggs during her

lifetime. With such a short

life cycle, several generations per year are possible, allowing this pest to develop

insecticide resistance.

In Arkansas, two seasonal population peaks occur, one in the late spring and one in the late summer or early fall. Adults emerge in mid-March with populations peaking in late May or early June. Horn fly presence or absence is temperature dependent, while abundance is influenced by humidity and precipitation. Therefore, during the dry and hot months of summer, populations normally decrease. In September, as temperature decreases and humidity and rainfall increase, populations will peak again.

Controlling Horn Flies

Complete elimination of horn flies is impractical and impossible. Monitoring horn fly populations is important in managing this pest. Populations are monitored by counting the number of horn flies on the heads, shoulders and backs of at least 10 cows.

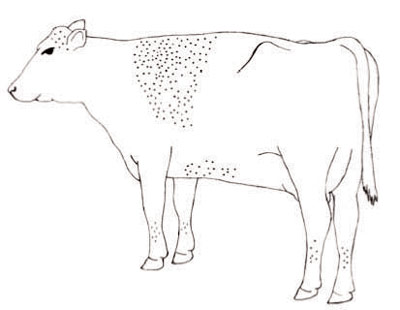

Most research suggests that economic damage occurs in dairy cattle when 75 to 100 horn flies per animal are present. For beef cattle, this threshold is about twice (150 to 200) that number. When average counts approach the economic threshold control or supplemental control should be considered.

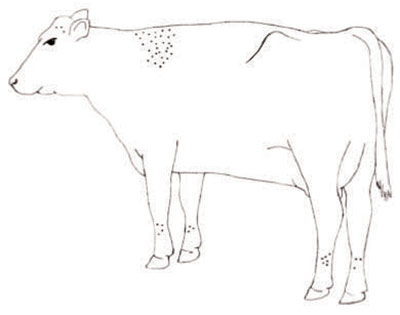

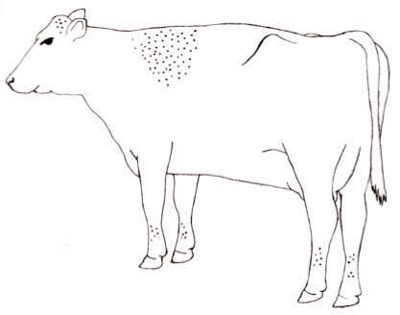

Figure 4a-c illustrates horn flies on cattle and may be helpful in estimating fly numbers.

Figure 4a. Illustration of a cow with 50 horn flies

Figure 4b. Illustration of a cow with 100 horn flies.

Figure 4c. Illustration of a cow with 200 horn flies

Horn fly control methods vary widely. Insecticide-impregnated ear tags, self-treatment devices such as back rubbers and dust bags, pour-on insecticides and sprays are the most common methods of applying contact insecticides. Other methods include feed additives containing insect growth regulators, walk-through sprayers and walk-through traps.

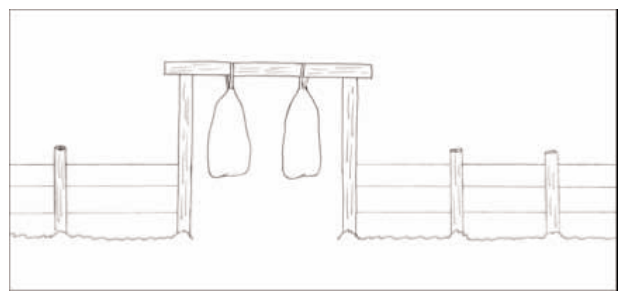

Walk-Through (Bruce) Trap

This is a non-chemical method that traps flies that are brushed off the animal as it passes through the trap. This will help control horn flies by dislodging the flies as the animal passes through the trap. Dislodged flies are trapped in elements located on the sides of the trap. Trapped flies cannot escape and die from starvation or dehydration.

The animals must pass through the trap to provide control; therefore, the traps are usually located in an area where animals must pass to gain access to water and/or feed, or in the case of dairy cattle, to travel to the milking parlor. During wet years, observe cattle to confirm use of the trap, as alternative sources of water may be available for the animals to drink; decreased use of traps will reduce their effectiveness for horn fly control.

In one Arkansas trial, an overall reduction of 57 percent of horn flies was noted when compared to an untreated herd. In another trial, the traps helped reduce the frequency of insecticide applications by 50 to 75 percent.

Consult your county Extension agent for plans on building these traps.

Insecticide-Impregnated Ear Tags

Insecticide-impregnated ear tags are applied to the ears of cattle and release a small amount of insecticide over a long period of time (Fig. 6).

If used properly, they can be an effective tool for controlling horn flies and ear ticks [such as the Gulf Coast tick, Ambylomma maculatum Koch, and the Spinose ear tick, Otobius megnini (Duges)] and may reduce face fly, Musca autumnalis DeGeer, numbers. Ear tags can provide about 12 to 15 weeks of continuous horn fly control.

Insecticide-impregnated ear tags are economical, easy to use and can provide long-term control but are often overused or misused, resulting insecticide-resistant horn flies. This misuse and other factors, such as the short generation time (2 weeks) and multiple generations per season (~10), contribute to insecticide resistance potential.

The active ingredients of insecticide-impregnated ear tags fall into five insecticide classes:

- synthetic pyrethroids

- organophosphates

- organocholorine (cyclodiene)

- macrocyclic lactones

- mixtures of the synthetic and organophoshpate insecticides

In addition to the active ingredient, several ear tags contain a synergist such as

piperonyl butoxide that increases insecticide toxicity to the horn fly. Since the

advent of insecticideimpregnated ear tags in the early 1980s, some horn fly populations

in the southern states have developed resistance to the insecticides used in the tags,

especially to synthetic pyrethroid and organophosphate ear tags, which for many years

were the only insecticide classes used in insecticidal ear tags. Insecticide resistance

or tolerance occurs because of the horn fly’s short generation time (every 2 weeks)

and multiple generations (more than 10) per year coupled with the

long residual activity of insecticide-impregnated ear tags.

If ear tags are going to be used, a few suggestions should be followed to help optimize effectiveness:

- Base ear tag application on the horn fly population and economic threshold (150-200

per animal for beef cattle and 75-100 per animal for dairy cattle). If ear tags are

applied too early, they may fail late in the season because of normal loss of insecticide

activity.

- Target control to get the most of your application. For example, treatment of lactating

animals will help maintain calf weaning weights.

- Rotate insecticide classes. Do not use the same insecticide class year after year.

Instead rotate among synthetic pyrethroid, organophosphate, organochlorine and macrocyclic

lactone insecticide classes. Remember, not all insecticide ear tags or classes are

labeled to use on lactating dairy cattle. Consult MP144, Insecticide Recommendations for Arkansas, for a listing of insecticide-impregnated

ear tags.

- Remove insecticide ear tags when they are no longer effective, when the label recommends

removal or in the fall.

- Read the label; don’t rely on ear tag colors or names to determine insecticide class.

Different brand names of tags may contain the same active ingredient. The label usually

suggests how many tags to use per animal. For face fly suppression and control of

ear ticks, one tag per ear (two per animal) is more effective.

- Consider other control methods such as self-treatment devices, sprays, mechanical

trapping,

feed additives or pour-on insecticides.

To mitigate potential insecticide resistance, rotate insecticide class and remove ear tags at the end of the fly season or when they fail. Also, if ear tags are applied too early, they may fail late in the season because of normal loss of insecticide activity or possible resistance.

Self-Treatment Devices

If properly used and maintained, self-treatment devices such as dust bags and back rubbers can be an effective and economical horn fly control technique. These devices allow cattle to treat themselves especially when they are forced use (moving through a restricted area on their way to feed or water). Specific synthetic pyrethroid and organophosphate insecticide dust and liquid formulations are labeled for use in dust bags, back rubbers and animal activated sprayers. Consult MP144, Insecticide Recommendations for Animals in Arkansas, for a listing on insecticides labeled for use in backrubbers or dust bags.

Dust Bags

Forced-use dust bags can be a very effective horn fly control method (Fig. 7). Insecticide dust is applied to the animal as it passes through an opening such as a gateway. Dust bags are constructed of close mesh fabric bags (usually heavy canvas or burlap and available commercially from most farm or feed outlets) that contain an insecticide dust. Inspect dust bags regularly and recharge with insecticide dust when needed. Dust bags should be kept dry to reduce insecticide clumping and loss of effectiveness

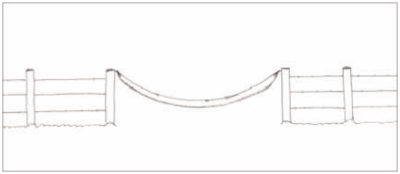

Back Rubbers

Back rubbers are used in much the same way as dust bags. A small amount of oil/insecticide solution is applied to the animal as it rubs under the device when passing through a gateway (Fig. 8). When charging or recharging a back rubber, use a good grade mineral or fuel oil (not motor oil) to mix with the insecticide. Mix the oil/insecticide solution according to label instructions.

Animal-Activated Sprayers

Animal-activated sprayers are similar to self-treatment devices in that the animal is treated on its way to or from a food or water source (Fig. 9). In most devices, the insecticide is sprayed onto the animal when the animal triggers a switch or electronic eye. These are used in gateways leading to minerals or water or as an exit sprayer in a dairy facility. Generally, only a small amount (less than 2 ounces) of insecticide is applied to the animal per application. Normally, animal-activated sprayers are only turned on when the fly population exceeds a pre-determined number (i.e., 100-150 horn flies per animal) indicating that routine monitoring of the horn fly population is necessary. Transportable, solar-powered devices are available commercially.

Figure 9a. Battery-powered automatic sprayer.

Figure 9b. solar-powered automatic sprayer.

Figure 10. Pour-on insecticide application.

Cattle often require acclimation to these animal-activated sprayers before they will routinely use the device. The device is usually placed in the off position in a gateway that animals must pass through for food or water. After cattle easily pass through the device in the off position, it can be turned to the on position so that cattle become accustomed to being sprayed. The acclimation process may take a week or longer.

Insect Growth Regulators and Larvicides

Insect growth regulators (IGR) and larvicides prevent horn fly larvae from developing into adults. These are administered to cattle as feed additives; immature horn flies (maggots) are exposed to these chemicals in the manure of cattle which consumed the product. Some formulations are available ready-to-feed, in the form of protein or mineral blocks or tubs, while others will require topdressing or custom blending. One IGR is available in a bolus labeled to provide larval control for up to 150 days. The mode of action of larvicides and IGRs differs. IGRs disrupt normal molting and development of immature horn flies (maggots) whereas larvicides are traditional toxins that kill the maggots.

Use of IGRs or larvicides is normally initiated just prior to the first appearance

of horn flies in the spring and throughout the summer and fall until cold weather

restricts fly activity. Proximity to untreated herds and adequate consumption by cattle

are two factors that can lead to variable results. To be effective, cattle must consume

a specified amount, preferably on a daily basis. If consumption is below the specified

rate, either increase the number of feeding stations or relocate stations to areas

more frequented by cattle. Likewise, if

consumption rate is above the specified rate, either decrease the number of feeding

stations or relocate stations to areas less frequented by cattle. Supplemental control

measures may be required if horn flies are moving in from untreated herds located

nearby. Diflubenzuron and methoprene are examples of IGRs; tetraclorvinphos is an

example of a larvicide. These products demonstrate similar effect on other flies (such

as face flies) developing in cattle manure. Consult MP144, Insecticide Recommendations

for Arkansas, for additional information on larvicides and IGRs.

Pour-On Insecticides

Pour-on insecticides are readytouse formulations applied along the back line of cattle at a dose based on body weight (Fig. 10). The concentration of the insecticide in a pour-on is usually higher than the final concentration used in a spray solution. Rates vary depending upon the insecticide formulation but usually range from 0.5 to 2 ounces per animal. Most conventional pour-on insecticides used against horn flies are formulated from synthetic pyrethroids. However, a few pour-on insecticides, macrocyclic lactones (ivermectin, etc.), are formulated to control internal parasites as well. Reliance on pouron macrocyclic lactones alone for horn fly control should be limited to lessen internal parasite tolerance issues. Pour-on insecticides will normally provide control from 2 to 4 weeks following application. Consult MP144, Insecticide Recommendations for Arkansas, for additional information on pour-on insecticides.

Insecticide Spraying

High-volume, high-pressure residual insecticide spraying is effective in controlling horn flies and other cattle pests (Fig. 11). About 1 to 2 quarts of an insecticide solution is applied with a power sprayer at a pressure of 150 200 psi. This amount and pressure will provide near complete coverage and penetration to the animal’s skin.

One drawback to high pressure spraying is the increased cattle handling required to make multiple applications throughout the fly season. Low-pressure, low-volume spraying with hand-held sprayers can be effective for some producers with gentle animals. With low-pressure, low-volume spraying, the applicator walks or drives around cattle applying an insecticide solution on an as-needed basis. Insecticide concentrates labeled to mix with water and apply to cattle primarily include the synthetic pyrethroid, organophosphate and spinosyn classes. Consult MP144, Insecticide Recommendations for Arkansas, for additional information on insecticide concentrates.

Remember to study the label prior to insecticide purchase and use. Some insecticides registered to use on beef cattle or non-lactating dairy cattle cannot be used on lactating dairy cattle.

The animal sections of MP144, Insecticide Recommendations for Arkansas, and Controlling Horn Flies on Cattle FSA7031, provide more detailed information on insecticides and horn fly control. Both are also available at your local county office.

Additional Resources

- Bugwood.org - Horn Fly Identification and Control

- Fly Control in Organic Dairies

-

Quick Reference Chart: Methods and Products for Controlling Horn and Face Flies on Beef Cattle