Direct to Consumer Beef Sales

Raising Calves for Slaughter

Rural landowners are often interested in raising calves to slaughter for personal consumption or local marketing. Advantages to raising your own calves for consumption include having control over calf quality and choosing how your calf is finished out. Disadvantages include the extra cost for the calf, supplies, and possible medical care as well as the extra labor that is required for raising cattle. One may also need to consider the emotional aspect of slaughter after raising an animal if they have children or become attached to animals easily. There is much to consider when raising a calf.

General Facility Considerations

Finishing (forage- or grain-finishing) and marketing goals (personal use or sale) will determine the land and facilities needed. Whether finishing calves on pasture or in a dry lot, calves will be more comfortable if they have access to shade during summer and a windbreak during winter. Even though calves grow adequately without shade or a winter windbreak, the necessity for access to shade and a windbreak is a personal preference depending on the level of animal comfort desired and marketing. If the goal is to market beef locally, buyers may be interested in farm tours to see where the beef was produced. Buyers of locally grown beef are in part making their buying decision based on their perception of how calves should be reared. If calves don’t have access to summer shade or winter shelter, someone will eventually make it a point to ask.

One farm-raised beef marketer noted that questions about water source and cleanliness were the most common questions received on their farm tour with clients. Earthen ponds are a good source of water for pasture-finished beef, but buyers may not like the idea of calves idling in ponds. Creating limited-access watering points can restrict calves from standing idle in ponds and also protect pond banks from eroding. If watering calves from small troughs, it is important to keep the troughs clean of manure, algae and foreign materials to sustain good water intake. Monitor tanks regularly to avoid winter freezing (add a heater if needed) and running dry during the heat of summer.

Cattle handling facilities, at a minimum, should include a catch pen with a lane and headgate to be able to vaccinate, treat illness, castrate and dehorn. Working facilities that are poorly designed and maintained can be a source of injury to both person and animal, and bruising may cause product loss. Walk through working facilities looking for possible points of injury, such as protruding bars, bolts or nails.

Finishing Options: Forage Versus Grain-Forage Finishing

The objective here isn’t to start a grass- or grain-finished debate; there is room for both in a local farm-raised beef market. It is important to understand common characteristics of forage- versus grain-finished beef when deciding which option is best for beef produced on-farm for personal use or market based.

What is the difference when cooked?

In general, the typical beef consumer in the U.S. enjoys the beefy flavor of grain-fed beef. By comparison, ground beef from cattle finished on forage has been characterized as having a “grassy” flavor. Grass-fed ground beef can also have a cooking odor that differs from grainfed beef. The visual appearance of the fat of grass-fed beef can be more yellow in color, due to carotenoids, in comparison to grain-fed beef fat that appears white.

What makes the beef lean or fatty?

Forage-finished cattle are usually finished at a lighter weight (approximately 1,000 pounds) than grain-finished cattle (approximately 1,250 to 1,450 pounds) and, as a result, are often leaner when delivered for slaughter compared to grain-finished cattle. Leaner beef is generally scored by taste panelists as being less tender and less juicy compared to fatter beef. So, the health-conscious consumer seeking forage-raised beef is usually willing to accept trade-offs of flavor, tenderness and juiciness for a leaner beef that may contain a greater proportion of heart-healthy fats. Whereas, other consumers may continue to seek the grain-finished beef characteristics but want to support local sources of grain-fed beef.

Forage-finishing capitalizes on the beef animal’s ability to convert forage cellulose into mammalian protein through the aid of microbial breakdown of forages in the rumen. Since cattle are naturally grazing animals, some producers and consumers prefer beef from cattle reared in their “natural environment.”

The first challenge to foragefinishing is having a sufficient area of grazeable land. Forage dry matter intake is thought to be maximized when forage allowance is kept above 1,000 pounds per acre. Forage-based systems may require 0.5 to 1.5 acres per calf, depending on fertilization, weed control, seasonal forage productivity and forage species management. Even with good forage management, hay is often needed for two to four months during winter. To sustain good calf growth rates and reduce the number of days required to finish calves on a forage-based system, high-quality hay should be offered when pasture grasses are limited. Supplementation with concentrate feeds, such as soybean hulls, may be needed to boost gains and allow for fat deposition when hay or pasture is moderate to low quality. Soybean hulls are recognized by the American Association of Feed Control Officials as a roughage source and are approved for grass-fed beef claims by the USDA for meat marketed as grass-fed beef.

The second limitation to forage-finishing is calf growth response. As forage quality, forage quantity and environmental temperatures fluctuate throughout the year, average daily gain may range from seasonal highs of greater than 2.0 pounds per day to seasonal lows of 0.5 pound per day. As a result, calves grown in forage-finishing systems are often slaughtered before they reach the same degree of fatness of grain-finished cattle. Forage-finished calves will often be slaughtered near 1,000 pounds live weight. It will take over a year (367 days) to grow a 500-pound calf to 1,000 pounds if its average daily weight gain is 1.5 pounds per day. Some extensive forage-finishing systems may require a longer duration for calves to reach slaughter weight if forage quality and quantity restrict growth to no more than 1 pound per day.

While ruminants have the distinct ability to convert cellulose into mammalian protein, there remains a history of fattening cattle on feedstuffs other than forage long before the establishment of the modern confinement feedlot industry. Early fattening in America included root crops, “Indian corn,” tree fruits and brewing and distillery mash. Confinement feeding in early America was also a mechanism to concentrate manure for fertilizer. Unlike forage-finishing, grain-finishing requires less land. Depending on soil type and topography, as little as 150 square feet per calf of pen space with a feed and water trough is sufficient. Producers of locally grown beef may sometimes allow a much larger area to keep grass cover in the lot instead of allowing the pen to become a dirt lot. This system is essentially a grain-finishing system on pasture. An example of such a system is described later.

When finishing calves in groups, 22 to 26 inches of linear trough space per calf is needed when all calves will be eating at once on the same side of the trough. Grain diets are much drier than pasture diets, and when calves are fed in confinement, they are usually watered from a trough. As discussed earlier, keeping the water trough clean is extremely important. A depression in water intake can cause a reduction in feed intake and slow growth rate. During hot weather, a calf near finishing weighing 1,000 pounds or more can consume in excess of 20 gallons per day.

Many associate grain-fed beef with corn-fed beef. From 2005 through 2011, corn use for ethanol grew to the point that the total use for ethanol reached that of feed and residual use. During this time, researchers examined the effect of increased use of corn distillers grains replacing dry-rolled, high-moisture and steam-flaked corn in feedlot diets. A feedlot finishing diet today may contain 6 to 12 percent roughage, up to 50 percent byproduct feeds (such as distillers grains and corn gluten feed), and cereal grains (mostly corn) representing 50 percent or more of the finishing diet.

Mimicking feedlot diets may not be practical when finishing calves on-farm for personal use or for local market; however, similar steps used in the commercial feeding industry should be adopted including: • Calves should be transitioned from a roughage diet to the final high concentrate diet over a three-week period. This is called a step-up program.

-

Feed calves at least twice per day when the final diet does not contain built-in roughage or is not formulated to be self-fed or self-limiting.

-

Include 10 to 15 percent roughage in the final diet for increased rumen health and reduced acidosis

- Feed Calves a balanced diet (protein, minerals, mineral ratios, and vitamins).

- Adjust feed amount as calves grow.

Consult with a nutritionist to develop a ration based on locally available ingredients or use a commercial finishing ration. Some feed mills offer “bull rations” that can also be used as a decent finishing ration. The “bull rations” sometimes include enough cottonseed hulls and byproduct feeds that additional roughage is not needed. Diets formulated for farm finishing can also be based on limit feeding the concentrate portion in the trough while allowing calves to have free choice access to pasture or hay for roughage.

What are other things to consider when raising calves for slaughter?

Calves selected for farm-raised beef vary in type. Budget, niches and end product goals will determine the type of calf that works best. Small-framed dairy calves like Jersey can have exceptional meat quality; however, percent retail product and size of cuts, like ribeye steaks, will be fairly small. A large-framed, heavy-muscled beef breed will have very good cutability (high percentage retail product), but calves of this type can take longer to reach maturity, will likely be slaughtered prematurely and freezer space may be inadequate to store all the cuts. Calves of beef breeds that are moderate-framed and early maturing with good muscling are ideal for most farm-raised beef programs. Producers who desire greater lean may desire calves of traditional Continental breeds like Charolais and Limousin; whereas, producers who desire the flavor and juiciness of steaks with more marbling (intramuscular fat that determines USDA Quality Grade) may prefer calves that are of predominantly of English breeds, such as Hereford, Red Angus, Black Angus or Shorthorn. Others prefer the novelty of certain breeds like miniature Herefords or Belted Galloways. Wagyu (which means Japanese cattle) is a breed type that has exceptional marbling.

Try to avoid finishing calves with more than 25 percent Brahman influence due to reduced cutability and tenderness. A nine-year summary of the Arkansas Steer Feedout program indicated calves that fit carcass targets for size, Quality Grade and Yield Grade had greater breed influence from English breed types and less breed influence from Continental breed types and Brahman breed influence.

Bulls should be castrated early in life, preferably at birth or by three months of age. Steaks from bulls can be leaner and tougher than steaks from steers. Aggressive activity of group-fed bulls can become a handling issue as well as increase chances for animal injury and bruising. Heifers make good farm-raised beef candidates. Heifers are often kept for breeding, and at the end of the breeding season, any heifer that did not become pregnant can be grown-out for slaughter. Heifers generally fatten quicker and have a slightly poorer feed conversion ratio than males.

A health program should include prevention of disease through vaccination and controlling internal and external parasites. Vaccinating and treating with antibiotics is not the same thing. Vaccinate calves to protect them against clostridial and perfringes diseases and viruses that are part of the respiratory disease complex (IBR, BVD, BRSV and PI3). Vaccine efficacy reaches its full potential when booster shots are given, so give booster shots when the vaccine label indicates a booster shot is needed.

Preventing Disease

Preventing disease is important, especially when trying to be a source of beef produced

from calves that were raised without antibiotics. When calves do become sick, it is

important to utilize antibiotics to restore health. Antibiotics are a component of

good animal husbandry, and calves that are treated with antibiotics can be marketed

as farm-raised without the antibiotic-free claim. Tissue damage from respiratory disease

and parasitism can rob calves of growth potential, lower feed conversion and increase

the cost of growing calves for beef. Visit with your local large animal veterinarian

or county Extension agent about product options and effectiveness for a complete calf

health management program.

Beef Quality Assurance

Cattle producers need to adhere to Beef Quality Assurance guidelines, and producers

looking to market farm-raised beef should acquire national or state Beef Quality Assurance

training and certification. As a producer of beef, administer shots subcutaneously

instead of intramuscularly when the drug label permits subcutaneous administration.

Always give shots in the neck region. Discard expired products, and always follow

the label instructions on slaughter withdrawal time.

Finishing Issues

Foot rot is a problem that can develop in both pasture and confinement finishing systems.

Calves finished on pasture may be exposed to toxic weeds and pastures with a high

percentage of legumes, which can result in bloat. To avoid pasture-associated problems,

never introduce hungry calves into a new pasture. Calves finished in confinement can

experience grain bloat and acidosis if fed a high percentage corn ration with inadequate

amounts of roughage in their diet. Calves that will be finished on a high percentage

grain diet should be transitioned from their forage diet to the high percentage grain

diet over at least a three-week period.

The final amount of retail cuts produced from a live calf will be affected by frame, muscle, bone, fat cover and gut capacity or fill. The first measure of yield is dressing percentage, which is the percentage of carcass weight relative to live weight. Dressing percentage can range from 58 to 66 percent. A 1,300-pound steer that yields a carcass weighing 806 pounds would have a 62 percent dressing percentage. A second measure of yield is retail product. The USDA Yield Grade is a numerical score that is indicative of retail product. A calculated Yield Grade is determined from hot carcass weight, fat thickness at the 12th rib, ribeye area and the combined percentage of kidney, pelvic and heart fat. Percentage of retail products can be calculated from these same measurements. Percent retail product may range from 45 to 55 percent. A 1,300-pound steer that is Yield Grade 3 would have a retail product percentage of 50 percent, which would yield about 650 pounds of retail product. If two individuals purchase a side of beef each, they each can expect 325 pounds of retail product. The yield of retail product will consist of approximately 62 percent roasts and steaks and 38 percent ground beef and stew meats. So, a single side of beef that yields 325 pounds of retail product would also yield approximately 201 pounds of roasts and steaks and 124 pounds of ground beef and stew meat.

Beef Cutout Calculator

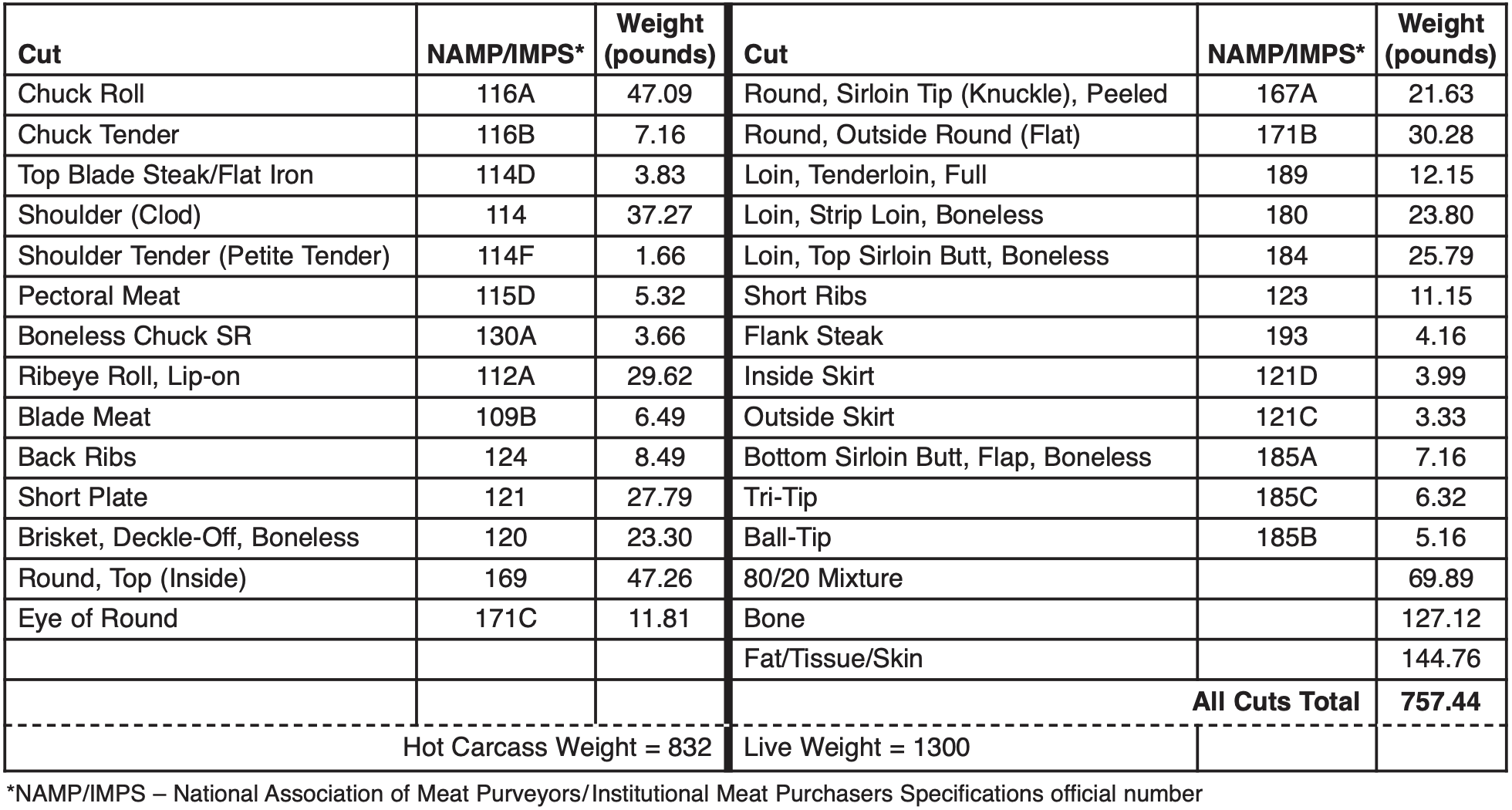

A useful tool for estimating product yield from a carcass is the Beef Cutout Calculator

(http://beefcutoutcalculator.agsci.colostate.edu/). User inputs include cattle type

(beef or Holstein), anticipated or known Quality Grade (Choice or Select), Yield Grade

options (calculated or selected from a range of Yield Grades) and weight (live or

hot carcass weight). The table below contains an example projected yield of wholesale

cuts using the Beef Cutout Calculator (prices excluded).

Beef Cutout Calculator Projected Cuts for a 1,300-Pound Live Weight, Choice, USDA Yield Grade 3.00 to 3.25 Range.

A plan for slaughter should be developed before a farm-raised beef program is initiated, especially if the intent is to market beef instead of growing out a single calf for personal consumption. In a 2001 survey of grass-finished beef producers, 40 percent utilized state inspection, 57 percent utilized federal inspection and 30 percent sold live animals for slaughter. Custom slaughter facilities are common in states such as Arkansas. However, beef packaged in many custom slaughter facilities cannot be retailed, and packaging must be labeled “not for sale.” Producers can opt to market finished live calves to buyers who are then responsible for coordinating custom calf slaughter. When the intent is to market packaged beef, processing must be done under federal inspection for interstate commerce. States offering state inspection have provisions for intrastate commerce. In Arkansas, for example, there are limited facilities that offer USDA slaughter inspection, and the state does not have a state inspection program. Whereas, Missouri is an example state with state meat inspection. The USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) maintains a list on their website of USDA-inspected facilities. Additional considerations for slaughter include:

- How many calves can the facility process (cooler space)?

- How many packages can be stored on-farm before market and delivery or use (personal freezer space)?

- How long will the facility chill carcasses before fabrication (aging)?

- Will the facility provide carcass details (backfat thickness, carcass weight, quality grade, yield grade) that can be useful for future calf selection and feeding management?

- What kind of packaging is available (butcher paper, vacuum packaging)?

- What specialty options are desired (jerky, sausage)?

- What processing costs are involved (slaughter fee, processing fee, specialty packaging fees)?

- Labeling products for resale under federal inspection.

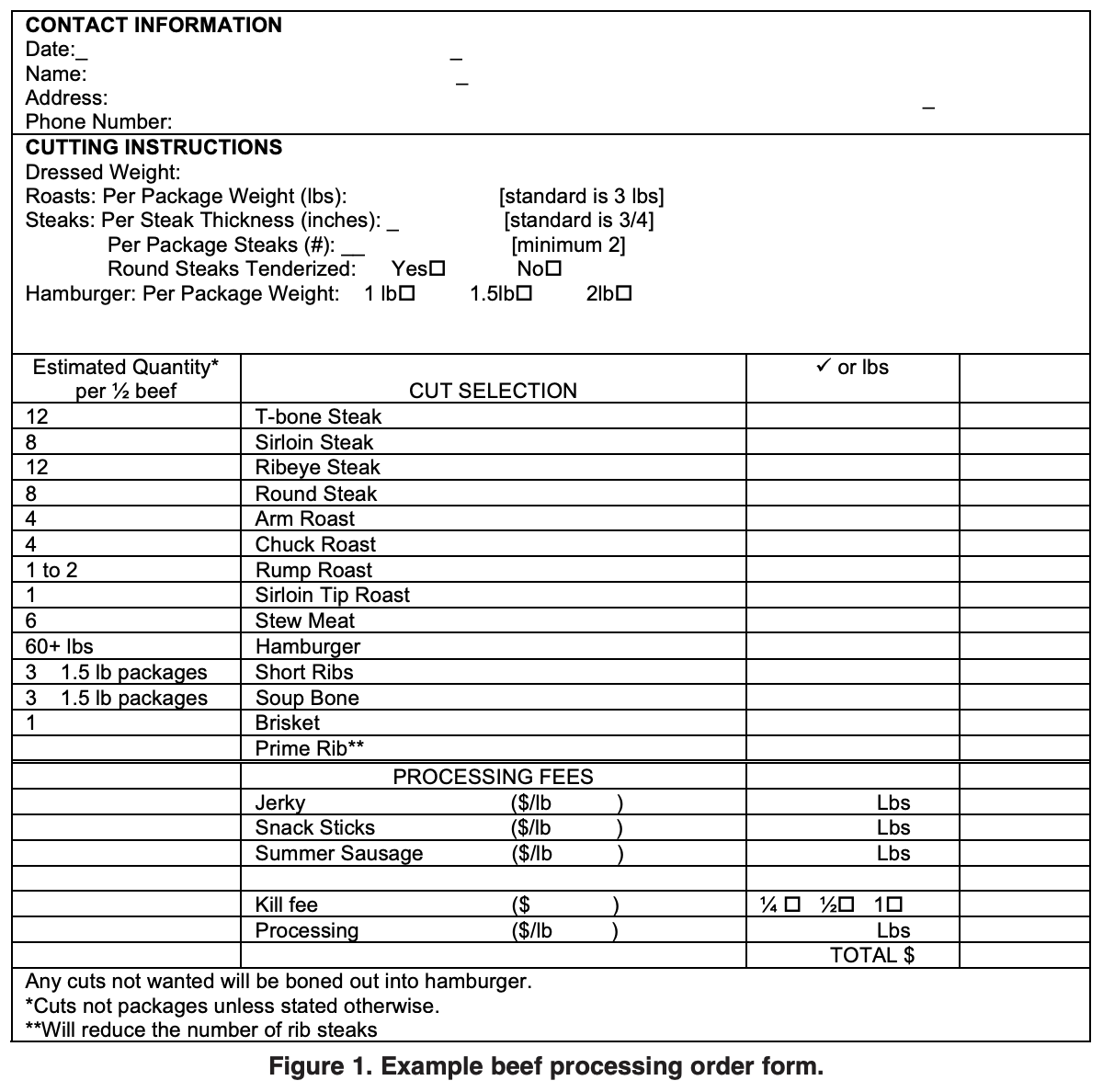

A component of custom slaughter is determining the type and size of cuts desired. One of the greatest challenges to selecting cuts and marketing farmraised beef is with the end meats (steaks and roasts from the shoulder and round). Middle meat (loin steaks like the ribeye) and ground beef demand is usually greater. Figure 1 is an example meat cuts form. For slaughter, customers can often specify steak thickness and package quantities, hamburger packaging weight, choice of steaks and(or) roasts or hamburger from the shoulder and round cuts. Some facilities may offer options such as jerky and summer sausage. Sometimes two or more buyers will go together to purchase a calf and evenly split the beef packages to accommodate freezer space and the amount of beef they consume.

Figure 1. Example beef processing order form.

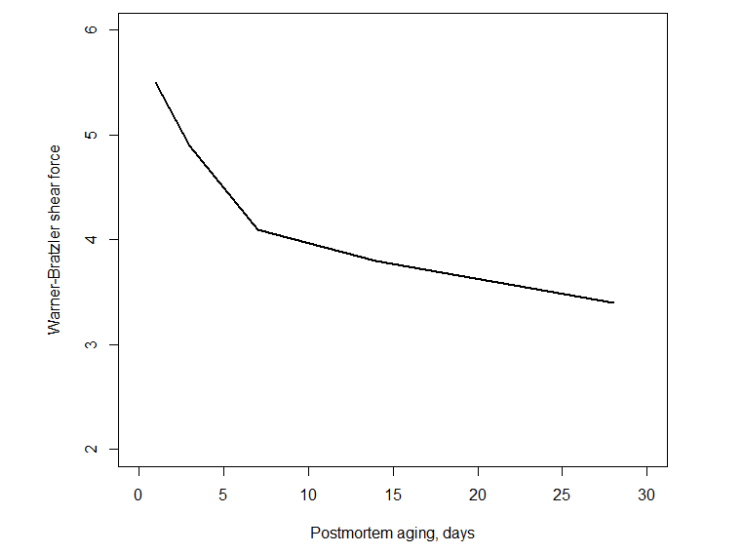

Effect of aging on forage-finished beef tenderness as determined by Warner-Bratzler shear force (adapted from Schmidt et al., 2013).

Producers intending to sell beef that was processed under state or federal inspection must first become promoters of product, not just producers of product. The majority of producers (95 percent) surveyed that market forage-finished beef sell to local individuals while 28 and 16 percent sell to independent stores and restaurants, respectively.

Most advertisement of forage-finished beef has been by word-of-mouth (99 percent); however, website (43 percent), direct mail (34 percent) and newspaper or magazine ads (25 percent) are also used for marketing. Contact local restaurants that emphasize locally produced menu items. Utilize social media tools, and create a farm website to promote your product and tell your story. Investigate shipping options. Most cities have farmers’ markets, but meat marketing will likely have a stronger customer base in urban areas. An important aspect of planning is to make sure product supply is not greater than product demand. An interstate program, MarketMaker, is a web-based resource to connect sellers and buyers of food products.

The concepts and details associated with economics and farm enterprise budgeting can easily be separated into a separate fact sheet. The purpose here is to present budget items to consider that would be associated with a farm-raised beef enterprise. The economics of farm-raised beef is often less important for the individual who is growing out a calf born on the farm to slaughter for family use. Individuals who intend to market beef should construct a finishing beef budget to evaluate the costs and returns to this farm enterprise. The contribution of the farm-raised beef enterprise to other farm enterprises will affect how certain fixed costs, such as equipment or facilities, are charged to the farm-raised beef program. A spreadsheet budget for finishing systems is available through Virginia Cooperative Extension, accessed July 29, 2016). Basic components of the finished beef enterprise budget should include:

1. Income

- Finished calf sales or meat sales

2. Expenses

- Initial calf purchase cost or cost to produce a weaned calf

- Pasture fertilizer, seed, and herbicide

- Land charge

- Purchased feed, hay, and mineral

- Veterinary care and cost of medicine

- Depreciation of facilities and equipment

- Hauling

- Meat storage, marketing, and distribution

- Hired labor

- Facilities maintenance and equipment repairs

3. Return

- Return to management and family labor

More Farm to Freezer Information

A Look at the UA System of Agriculture Red Meat Abattoir

Farm to Freezer Presentations

Do's and Don'ts of Meat Processing

Arkansas Beef Council Retail Production Report May 2020