Encountering Native Snakes in Arkansas

People fear snakes more than any other wildlife species in Arkansas.

According to psychologists and animal behaviorists, the fear of snakes is a learned behavior. Research indicates our brains are pre-conditioned to readily accept this fear. Statistically, however, deaths from venomous snakebites are rare.

With quick medical treatment, the vast majority of victims survive. Obviously, avoiding encounters with snakes will decrease the odds of being bitten.

Arkansas Native Snakes

Snakes serve an important role in our environment. They prey on rodents, insects, toads, frogs, crayfish, minnows and other snakes. Snakes are themselves food for hawks, owls, foxes, bobcats, raccoons, fish and many other species.

Of the 39 species of native snakes in Arkansas, only six are venomous (Table 1). Several excellent resources are available for identifying snakes.

- Copperheads and Similar Looking Harmless Species — Virginia Herpetological Society

- The Amphibians and Reptiles of Arkansas by Stanley E. Trauth, Henry W. Robison and Michael V. Plummer. The University of Arkansas Press. 421pp.

- Arkansas Snake Guide – available free from the Arkansas Game & Fish Commission (800-364-4263) or download electronic guide.

- Herps of Arkansas web site sponsored by the Arkansas Herpetological Society.

People mistakenly kill snakes when in fact they pose no threat. Most venomous snakes are slow to strike and do so only if provoked. Typically, snakes will go to great lengths to avoid a confrontation with people. A study of cottonmouths in the field (45 snakes) and laboratory (36 snakes) found half of the snakes encountered in the field tried to escape. In the lab where escape was not an option, over three-fourths used threat displays and about a third (13 of 36) bit an artificial hand used in the tests.

Some nonvenomous snakes share common characteristics with venomous snakes, perhaps to appear more threatening. The nonvenomous eastern hognose or “puff adder” will increase its head size and emit a smelly musk (Figure 2).

If this doesn’t cause the threat to leave, the snake will roll over and play dead. The hognose, and some nonvenomous snakes, have color variations and patterns that can be mistaken for rattlesnakes. Some will vibrate their tails against dead leaves, making rattlelike sounds. Although these characteristics are intended to improve survivability, these adaptations may lead to the opposite outcome when snakes encounter snake-intolerant people.

Venomous Versus Nonvenomous Snakes

Venomous native snakes present in Arkansas are the:

- eastern copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix)

- northern cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus)

- western diamond-backed rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox)

- timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus)

- western pigmy rattlesnake (Sistrurus miliarius)

- Texas gulfcoast coralsnake (Micrurus tener)

Table 1. Venomous snakes of Arkansas

| Image | Species | Characteristics | Habitat |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Eastern |

Tan with darker brown hourglass-shaped bands. Bands sometimes thinly bordered with white. Belly mostly patternless but some times with lower spots between bands extending onto belly. Heat-sensing pits. Pupils elliptical. Juveniles with bright yellow tail. Peas (Southern) | Occurs statewide in mixed pine-hardwood forests, bottomland hardwood forests, rocky or brushy fields and hillsides. |

|

Northern |

Aquatic. Black or with dark, obscured patterning. Dark stripe from nostril to neck. Labial scales lighter and without vertical bars. Heat-sensing pits. Pupils elliptical. May gape white “cotton mouth” when disturbed. Buoyant swimmer. Juveniles with bold pattern contrast and bright yellowish-green tail. | Occurs statewide in variety of wetland habitats: swamps, oxbow lakes, sloughs, drainage ditches and streams. |

|

Western Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) |

Mottled brown, tan and black with large, roughly diamond-shaped middorsal blotches. Blotches thinly etched with white except toward tail. Heat-sensing pits. Eyes elliptical and between light, diagonal stripes. “Coon tail” with rattle. | Occurs in west-central Arkansas in upland rocky, open pine-hardwood forests and rocky outcrops. |

|

Timber Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) |

Grayish, yellowish or light brown background with dark, jagged crossbands and rust-colored mid-dorsal stripe. Head with darker band from eye to jawline (less obvious in some individuals). Heat-sensing pits. Eyes elliptical. “Velvet tail” with rattle. | Statewide in hardwood, mixed pine-hardwood, bottomland hardwood forests and rocky or brushy fields and hillsides. |

|

Western Pigmy Rattlesnake (Sistrurus miliarius) |

Smallish. Gray with black cross-bands and rust-colored middorsal stripe. Crossbands usually incomplete with gaps along sides of body. Head boldly patterned. Heat-sensing pits. Eyes elliptical. Diminutive rattle. | Statewide in open brushy lowlands, open hardwood and mixed pine-hardwood forests. |

|

Texas Gulf-Coast Coralsnake (Micrurus tener) |

Rare. Alternating black, red and yellow bands so that “red touches yellow.” Bands extend onto belly. Red bands often with specks of black. Snout all black and stubby with next band being yellow. | Occurs in southwestern portion of state in moist pine, hardwood or mixed pine-hardwood forests with loose, sandy soils and pine straw, leaf litter and logs for cover. |

Top five photos by Kory Roberts. Bottom photo by Kelly Irwin with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission. Adapted with permission from Herps of Arkansas website, and Arkansas Snake Guide by the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.

All except the coralsnake are in the family Crotalinae, also called pit vipers. Pit vipers have retractable fangs to inject venom which subdues prey.

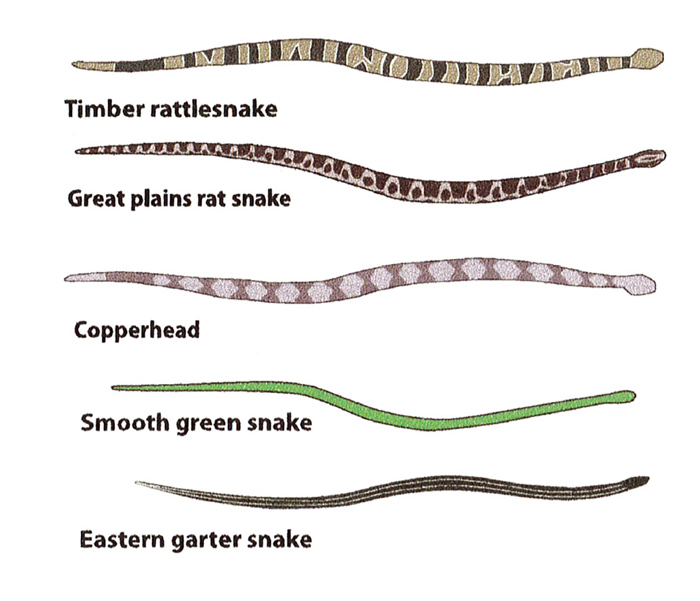

The best way to identify venomous snakes is by their color patterns (Figure 3). Many nonvenomous snakes are mistaken as venomous. Some possess color patterns which mimic venomous snakes (Figure 4). This is especially true for juveniles which may not resemble adult coloration.

Figure 3. Color patterns of venomous versus nonvenomous snakes. Illustration by Chris Meux.

Venomous native snakes in Arkansas have distinctive color patterns (Table 1). Other clues may be a triangular head shape, vertical pupils in sunlight (i.e., “cat eye”), and body thickness.

Some nonvenomous snakes also have triangular heads and thicker bodies, so coloration is key! Pit vipers have a hole (pit) between the eye and nostril which requires close examination and therefore it is not recommended for identification in the field.

How can I identify the Texas coralsnake?

A Texas gulfcoast coralsnake is very colorful and easily distinguished from the pit vipers.

Some nonvenomous snakes have similar colored bands of red, black, yellow or white. Remember the saying, “red touch black - venom lack; red touch yellow - kill a fellow,” to prevent mistaken identity. Keep in mind its range is only a small portion of southwest Arkansas. The reclusive nature of coralsnakes results in few encounters.

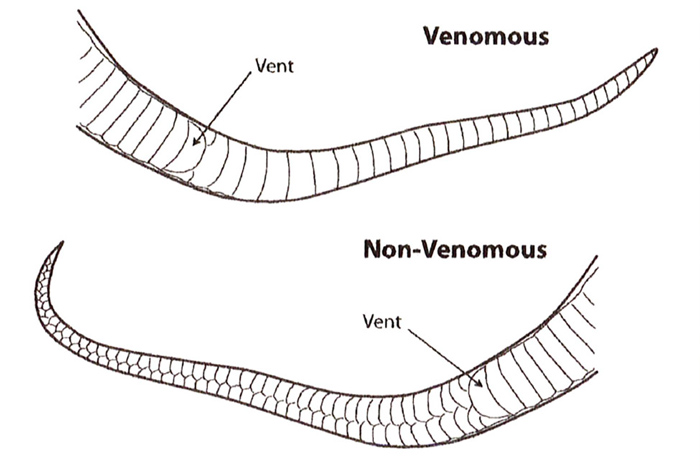

Can I identify a snake by it's shed skin?

If you happen to find an intact shed of a native snake’s skin, observe the tail section from the vent (where feces is expelled) to the tip (Figure 5). The scales for nonvenomous snakes will be broken in half, whereas venomous snakes will be whole. The underbelly scales from vent to tail will appear the same as those in front of the vent. Some sheds may hold clues to the snake’s identity. The shed of a speckled kingsnake, for example, will often have a small dot in the middle of each scale.

Figure 5. Tail characteristics of venomous and nonvenomous snakes in Arkansas. Illustration by Chris Meux.

Snake Venom

Snakes that bite to inject toxins in their prey are called venomous. Venom is used to subdue their prey. The amount of venom injected will vary. In some instances, snakes perform “dry bites” in which no venom is injected.

The venom of pit vipers is hemotoxic, which means it destroys red blood cells, capillaries and tissue. Rattlesnake venom is the most severe of the pit vipers.

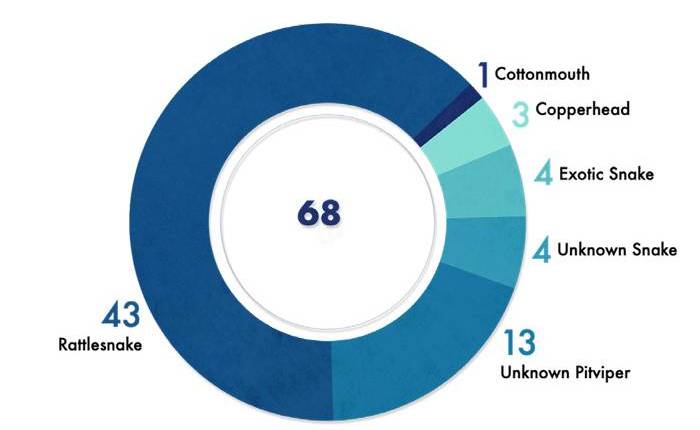

Nationally, rattlesnakes account for the majority of snakebites (Table 2). Rattlesnakes accounted for at least 43 (63 percent) of 68 reported snakebite deaths in the United States from 1983 to 2018. Case studies indicate several were caused by a combination of alcohol consumption and poor judgment, or an allergic reaction to the antivenin.

Table 2. Number of fatalities caused by venomous snakes in the United States from 1983-2018 reported to Poison Control Centers.

American Association of Poison Control Centers.

No deaths were recorded from Texas gulfcoast coralsnakes at the time of publication. The coralsnake has potent venom which is neurotoxic, attacking the nervous system of its prey. Venom is injected through short fangs requiring the coralsnake to bite and chew its prey. Fortunately, coralsnakes are usually docile and seldom bite when disturbed. Few people encounter coralsnakes because of their highly secretive habits in forests in southwestern Arkansas.

How do I avoid snake encounters?

Understanding snakes and their habits can help with avoiding being bitten. Oftentimes movies and the media play upon people’s fear of snakes. Snakes do not purposefully try to do harm. A venomous snake observed from a distance and left alone is completely harmless.

Most snakebites occur when snakes are harassed or threatened, such as when attempting to harm or kill them. Snakes have only a few means of defense. Most rely on their camouflage. A study by the Missouri Department of Conservation reported copperheads tracked with radio telemetry avoided human activity. When humans were nearby, copperheads remained quiet to avoid detection as their primary defense. A snake’s camouflage makes them well-suited to hiding undetected in locations where prey species are likely to be present. Snakes wait for their prey underneath or beside logs, rocks and debris.

Be snake aware and use these tips to avoid snakes:

- Walk on paths with clear visibility and little ground cover where snakes may be easily

seen. If at night, use a light source to brighten your path.

- Never step over logs or other obstacles unless you can see the other side.

- Watch where you put your hands. Don’t put fingers under debris you intend to move.

Flip with a wooden pole to make sure a snake isn’t hidden underneath.

- Make noise and be wary, particularly of where your foot is about to step.

- Carry a walking stick to clear away leaves, make noise, flip objects, and keep balance

when peeking over logs or other obstacles before crossing.

- Wear close-toed shoes or boots. Many snakebites result when walking barefoot or wearing

sandals around the yard. Consider wearing snake proof boots or leggings when in areas

known for snakes.

- Pattern your outdoor activity to avoid snakes. Snakes are ectothermic or “cold-blooded,”

which means their body temperature is similar to their surroundings. Most snakes prefer

to maintain body heat at about 86 degrees F, though they are active in temperatures

ranging from 50 to 104 degrees F. Snakes seek particular locations to regulate their

body temperature.

- In the heat of the summer, snakes are more active at night and seek cooler areas for

daytime retreat. When walking at night in the summer months, use a flashlight.

- In the late fall and early spring, snakes seek rocks or patches of sunlight to bask and heat their bodies. They tend to be more active during daylight hours. Be snake alert when walking through rocky areas or leaf litter, which can camouflage a snake.

- In the heat of the summer, snakes are more active at night and seek cooler areas for

daytime retreat. When walking at night in the summer months, use a flashlight.

If you encounter a snake, step back and allow it to pass. Snakes usually don’t move fast, and you can retreat from the snake’s path.

How do I deal with snake problems?

There are several options for dealing with snake problems including habitat modification, exclusion from buildings, capture/release of nonvenomous snakes, constructing a snakeproof fence or birdhouse and leaving them alone.

Habitat Modification

If snakes are a problem, keep snakes from your yard by mowing the lawn regularly and removing piles of logs, brush, rocks or debris where mice and other prey may live. Eliminate cool, damp areas where snakes hide. Keep mulch in flower beds to a minimum and avoid low-growing plants, particularly near the home. Controlling for insects and rodents can help control snakes. See Controlling Mice and Rats MP546. Avoid leaving dog food, cat food or excess seeds from bird feeders outside. Keep grains or other rodent attractants in sealed containers, and set mouse traps to control rodents around your home.

Exclude from Buildings and Chicken Houses

Use caulk, weather stripping, spray foam, mortar or other material to seal small openings around foundations and spaces around plumbing pipes, heating, cooling and electrical ducts. Snakes can enter a hole the size of a dime, so seal every possible entry.

Capture and Release of Nonvenomous Snakes

Nonvenomous snakes found indoors can be removed from your property and relocated.

- Nonvenomous snakes can be removed legally from your property and relocated outside

of city limits within 24 hours of capture. It is not recommended that you capture

snakes by hand.

- In basements or outbuildings, place a pile of damp burlap sacks in a corner to concentrate the snakes. Place a dry sack on top to keep the moisture from evaporating. The next day, use a shovel to move the pile of bags outdoors and release the snakes.

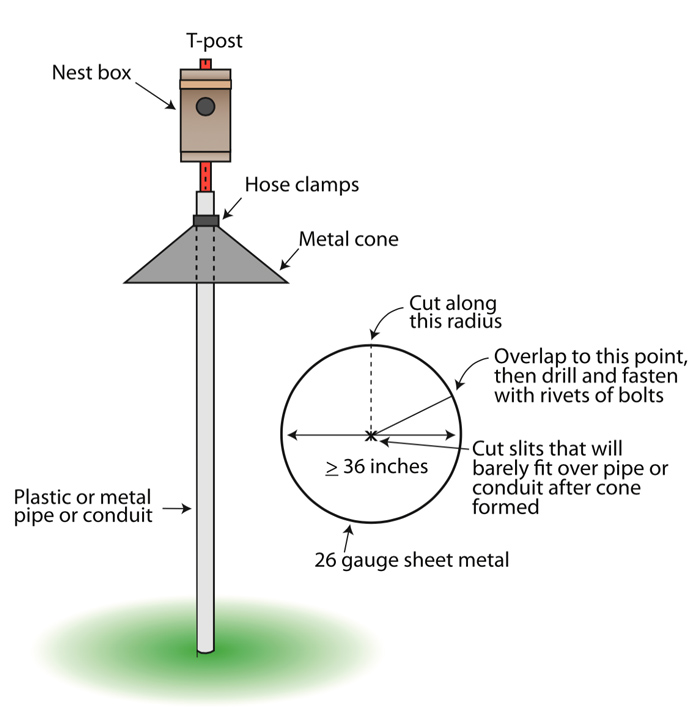

Snakeproof Birdhouses

Snakes are adept at climbing and eating bird eggs and fledglings. Snakes can climb smooth poles, even ones that have been greased. A cone guard mounted on a metal pole or PCV pipe can be effective at deterring snakes. Cone guard baffles can be purchased where wild bird supplies are sold or made from galvanized sheet metal (Figure 6).

Figure 6. A cone guard or baffle can prevent snakes from entering songbird nest boxes. Illustration by Chris Meux.

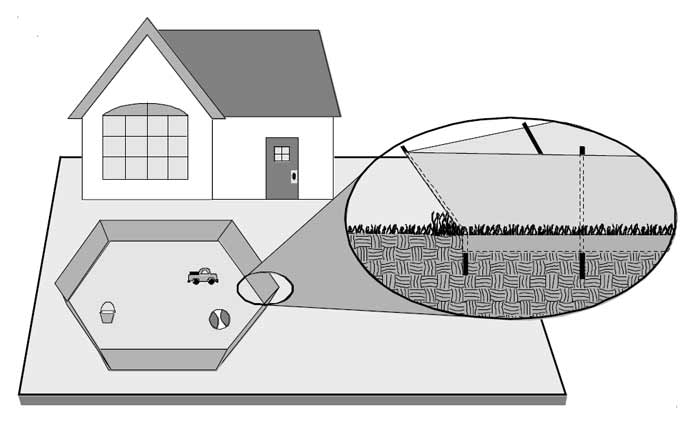

Snakeproof Fencing

Under certain circumstances, such as a small backyard, lakeside yard or play area, constructing a snakeproof fence is an option (Figure 7). Use 36-inch high galvanized hardware cloth with a 1/4-inch mesh. Bury the fence 6 inches deep and slant outward at a 30-degree angle. The gate should fit tightly and swing into the area. Clip vegetation around the fence to keep snakes from crossing over.

Figure 7. A snakeproof fence can be an option for enclosing small areas. Illustration courtesy of University of Missouri Extension.

Repellents

No repellents have proven effective for snakes. Dr. T’s Snake-A-Way (7 percent naph thalene and 28 percent sulfur), a commercial snake repellent, has not proven successful in repelling western rattlesnakes and plains garter snakes. Several potential home remedies have been tested on black rat snakes and have also proven ineffective. These include gourd vines, moth balls, sulfur, cedar oil, a tacky bird repellent, lime, cayenne pepper spray, sisal rope, coal tar and creosote, liquid smoke, artificial skunk scent and musk from a king snake (which preys on other snakes).

Leave Alone

If the snake is not causing harm, oftentimes the best response is to simply leave it alone. Prodding or handling a snake increases the risk of a snake bit. Some nonvenomous snakes consume rodents and other snakes (Figure 8), including venomous snakes. Having nonvenomous snakes around could be beneficial.

Killing a snake is not recommended!

Many people get bitten in the process of trying to kill a venomous snake. Leaving a snake alone often is the best option. If lethal removal is necessary, a venomous snake should be struck with a long stick, rod or other tool, such as a garden hoe. Keep out-side of the snake’s striking range, which is usually less than one-half the total length of the snake.

Be cautious when removing the snake. A dead pit viper, even if it has been decapitated, can bite and inject venom for several hours after the initial blow. Placing a warm object, such as a hand, near the snake’s mouth may trigger a biting response.

Is it illegal to kill a snake in Arkansas?

All native snakes, including venomous snakes, are protected by law. Evidence indicates some snake species are declining due to habitat destruction and human activities. The Arkansas Wildlife Action Plan identifies snake “species of concern” because of declining numbers, including two venomous species, the western diamond-backed rattle-snake and the coralsnake, both venomous species.

The Arkansas Game and Fish Commission enforces regulations which prohibit killing nongame species, including venomous and nonvenomous snakes, except under limited circumstances. Commission code allows nongame wildlife (excluding bats, migratory birds and endangered species) that pose a reasonable threat to persons or property to be taken. Presumably a venomous snake which is endangering others, especially children, can be dispatched.

Arkansas law does not allow killing of any snake indiscriminately for sport or other reasons. Instances where intent or motive are unclear may be decided in a court of law.

Venomous Snakebite

If bitten by a venomous snake, move away to avoid further bites. Do not attempt to catch or kill the snake, as this could result in additional snakebites and also wastes time when treatment is the priority.

An antivenin is available for all native pit vipers, so it is helpful, but no longer imperative, to determine the particular species of pit viper. If there is uncertainty whether the snake is a pit viper, check the injured area for one or two (and on rare occasions three) fang marks in addition to teeth marks. Typically, there is swelling and pain in the bite area, followed by black and blue discoloration of the tissue and possibly nausea.

What should I do if I've been bitten by a snake?

- Remain calm so as not to increase blood circulation and spread venom more quickly

throughout the body.

- Remove rings, watches, bracelets, shoes and other restrictive clothing near the bite.

- Seek medical attention immediately! Call ahead, if possible, to alert medics, or call

your local emergency medical facility if you need transportation.

- Keep the bite area immobilized as much as possible.

- Do NOT apply ice.

- Do NOT make cuts.

- Do NOT apply a tourniquet.

- Wash the bite site with alcohol or soap and water, if available. Be sure to wipe in the direction away from the wound.

A snakebite victim may go into shock if the tissues in the body do not receive enough oxygen or nutrients. Symptoms of shock are:

- skin becomes clammy and pale

- confusion or loss consciousness or chest pain, as the heart isn’t receiving an adequate oxygen supply

Lay the person down in a safe place and try to keep him or her warm until emergency assistance arrives.

If a coral snakebite is suspected, seek immediate medical attention. Because of their tiny teeth, a coral snake’s bite is difficult to detect. Their bites, though rare, are easy to miss. They are painless, with little change in the surrounding tissue. Local numbness may occur and breathing will become labored. As symptoms progress, these symptoms may become more difficult to reverse medically.

Although exotic venomous snakebites are rare, fatalities do occur. Keepers of exotic snakes should keep venom protocols. Seek immediate medical attention and alert medics quickly as it may be difficult to find anti-venin for these less common, nonnative snakes.

What should I do if I've been bitten by a nonvenomous snake?

If bitten by a nonvenomous snake, treat the wound as you would any minor scrape or cut. Keep it clean and apply antibiotics to reduce the risk of infection. A bite from a nonvenomous snake may feel like a pinch or pin prick and may itch, but it shouldn’t sting like a venomous snakebite.

The bite wound will correspond with the rows of sharp, pointy teeth found in a snake’s mouth. The bite may bleed more than one might expect due to the sharpness of the teeth and anticoagulant properties of the snake saliva.

Reference to commercial products or businesses is made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement by the University of Arkansas is implied.

To see references or print this information download our publication Native Snakes of Arkansas FSA-9102