Peanut Diseases and Control

Seedling diseases are caused by several soilborne fungi, but the most common are Pythium and Rhizoctonia solani. These fungi cause pre- and post-emergence damping off. Seedlings infected with Pythium spp. rapidly collapse from root decay, often with a sloughed outer root layer. This pathogen can be problematic when cool, wet conditions persist after planting. Seedling infected with R. solani exhibit a dark, sunken lesion just below the soil line. Rhizoctonia is often more problematic in warm soils. Seedling disease can contribute to a poor stand, which is why all peanut seed are sold with a seed-applied fungicide (Fig. 1). Seed applied fungicides are effective at minimizing losses to seedling diseases, but other factors can contribute to a poor stand like herbicide injury, excessive rain, and poor quality, so be sure to determine the cause of the poor stand before implementing management practices.

Figure 1. Thin stand due to seed without a seed-applied fungicide (center), without a seed-applied fungicide and infested with Rhizoctonia (right), and seed with a seed-applied fungicide and infested with Rhizoctonia (left).

Early leaf spot is a foliar disease of peanut that can cause significant losses in pod yield. Leaf symptoms consist of circular, brown to dark brown lesions surrounded by a yellow halo (Fig. 1). Symptoms can develop on petioles and stems when disease development is severe. Early leaf spot is caused by the fungus, Passalora arachidicola (syn: Cercospora arachidicola) that produces silvery, fuzzy tufts of spores on the top side of the leaf (Fig. 1). These tufts can be seen without magnification, but a 20x hand lens is helpful. Looking for these tufts of spores is helpful to differentiate early leaf spot from all the spots that show up on peanut. The fungus overwinters in peanut debris, so a three-year rotation system (two year of other row crops) can help to reduce inoculum for the subsequent peanut crop. Well-timed fungicides are effective, but fungicide-resistance is a concern, so follow fungicide resistance management strategies. For those strategies and fungicide efficacy information, see the Arkansas Plant Disease Control Products Guide .

Figure 1. Early leaf spot of peanut on Spanish peanut cv. OLin near Newport, AR. Note tufts of spores in the center of a few leaf spots.

Late leaf spot (caused by Notholopassalora personata (syn: Cercosporidium personatum)) is the most common leaf spot disease in Arkansas. Since 2017 several fields were reported to have significant defoliation. Leaf symptoms consist of circular, brown to dark brown lesions without a yellow halo (Fig. 1). Symptoms can develop on petioles and stems when disease development is severe (Fig. 2). Sporulation of late leaf spot occurs on the bottom of the leaf surface as small groups of pseudoparenchymatous stroma. The onset of disease development typically begins in September, but can occur earlier when conditions favor disease development. Though some cultivars are moderately susceptible (Georgia 06G, Georgia 16HO and AUNPL 17) others are susceptible, thus fungicides are often used to manage this disease. Well-timed fungicides are effective, but fungicide-resistance is a concern, so follow fungicide resistance management strategies. For those strategies and fungicide efficacy information, see the Arkansas Plant Disease Control Products Guide.

Figure 1. Late leaf spot of peanut on runner-type peanut near Manila, AR. Note stroma are visible on lower leaf surface in the center of a few leaf spots.

Figure 2. Severe late leaf spot symptoms on peanut.

Leaf scorch is a very common foliar fungal disease of peanut in Arkansas. It is a minor disease as it rarely causes any yield losses. Leaf scorch and pepper spot are caused by Leptosphaerulina crassiaca. Both are minor disease of peanut in Arkansas that do not warrant a fungicide. Leaf scorch can looks impressive in the field, but does not cause a significant amount of defoliation. It may develop along the leaf edge or more commonly in the center of the leaf resulting in the “v-shaped” lesion with yellow margin (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Leaf scorch of peanut caused by fungus Leptosphaerulina cassiasca, a minor foliar disease that does not warrant a fungicide.

Sclerotinia blight is caused by S. minor and S. sclerotiorum that were first reported in 2013 and 2014, respectively, in commercial peanut fields in Arkansas. Yield losses by this disease are significant (>80%) in areas of the field where disease incidence and severity are extensive. Yield loses are often related to pods loss in the field. Field wide average yield losses range from 10-20%. Currently, Sclerotinia blight has been reported in Randolph and Lawrence counties. Of the two pathogens S. minor is the more aggressive pathogen on peanut and contributes to a greater yield loss.

Wilting or “flagging” of the apical tips of the main stem or branches if often the first symptom observed in the field (Fig. 1). The symptom is similar to that of southern blight, but with Sclerotinia the leaves are curled rather than clasped together as with southern blight. With a closer inspection, the infected stems are often bleached with white fluffy hyphae surrounding the infested stem (Fig. 1 and 2). Hyphae often become matted around the stem later in the afternoon, when conditions are drier and warmer (Fig. 1 and 2). Black sclerotia can be found on and inside infected stems (Fig. 3). These range in size from no. 8 to no. 4 lead shot and often misshapen like coarse ground black pepper. Over the past seven years symptoms have begun as early as August and as late as October with cool temperatures being the primary factor in the onset of disease development. Sclerotinia blight is often observed after the high temperatures remain below 83°F for a couple days

As with all soilborne diseases prevention is the best way to keep the infectious propagules from entering a non-infested field. The pathogen can be transported in soil or peanut vines that hitch a ride on cultivation or harvesting equipment, so clean recently purchased, used equipment from excess mud or peanut debris, especially if came from an area where the disease occurs. Sclerotinia blight has been reported from Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas. A three-year crop rotation can help to reduce inoculum (sclerotia) densities with a longer rotation needed in fields with significant yield losses from Sclerotinia blight. Avoid soybean in rotation as it is a host for Sclerotinia blight; however, soybeans are senescing by the time conditions favor soybean infection in Arkansas. Fungicides can be used to mitigate disease severity but they are often more expensive ($50.00 +/acre), thus prevention is a cheaper options. See MP 154 for information on fungicides. Timing is important for disease management and should begin prior to disease development. Fields with a history of disease should begin a fungicide program in August, especially if cool weather is in the forecast. Peanut cultivars vary in susceptibility to Sclerotinia blight, but most are considered susceptible. The University of Arkansas, Lonoke Extension Plant Pathology program is currently screening cultivars at the Newport Extension Station, where Sclerotinia blight was found in research plots.

Figure 1. Initial flagging caused by Sclerotinia blight of peanut. Note leaves are curled.

Figure 2. White hyphae produced by Sclerotinia minor on infected peanut stems.

Figure 3. Black sclerotia produced by Sclerotinia minor on the surface of infected peanut stems. Sclerotia are the size of no. 8 to no. 4 lead shot.

Rhizoctonia limb rot is a late season disease that is more severe in furrow-irrigated fields or after extended period of wet environmental conditions. Though it has been observed in Arkansas it is not as common as southern blight. Symptoms consist of elongated, dark brown target-patterned lesion on stems and lower branches near the soil (Fig 1). Affected stems may wilt under hot conditions and die whereas the remaining plant appears unaffected. Pegs and pods may also be infected. Rhizoctonia limb rot is caused by a soilborne pathogen, Rhizoctonia solani AG-4, which overwinters in crop residue and in soil as sclerotia. Crop rotation with corn or sorghum can minimize inoculum for subsequent crop and timely applied fungicides can be effective at protecting yield potential. Fungicides used for Rhizoctonia limb rot are often effective for southern blight, thus producers can target multiple peanut diseases with some fungicides.

Figure 1. Lesion with concentric rings caused by Rhizoctonia limb rot.

Southern blight is also called Southern stem rot, stem rot, and white mold commonly occurs at midseason (July or August) when foliage covers the furrow. This is one of the most widespread diseases of peanut in the U.S. and is the most common soilborne disease of peanut in Arkansas. Yield losses can be significant when disease severity is high.

The first symptom observed in the field is “flagging” or wilted leaves (Fig. 1). The “flagging” is similar to that of Sclerotinia blight but the leaflets are often collapsed together, “wilted” as if water was a limiting factor. The “flagging” symptom is most commonly observed in July in Arkansas. With closer inspection near the soil line, a white fanlike mat of fungal mycelium can be seen at the base of symptomatic plants along with numerous small round fungal fruiting bodies (called sclerotia) that are about the size of a mustard seed or size of no. 9 (2 mm) to no. 4 (3 mm) lead shot (Fig. 2). Immature, sclerotia are yellow-tan then progress to reddish-brown and finally dark brown at maturity. Southern blight is caused by Athelia rolfsii (syn: Sclerotium rolfsii) that has a host range of ~ 200 species. The pathogen overwinters as sclerotia that can remain viable for three to four years near the soil surface. Disease is favored by hot (77-95°F), humid weather conditions.

Figure 1. Wilted peanut plant stems infected with southern blight.

Figure 2. Numerous reddish-brown sclerotia and white mycelium of Sclerotium rolfsii near the peanut crown.

Management of southern blight consists of preventing inoculum buildup by rotation with corn or sorghum. Soybean is a good host for Sclerotium rolfsii and other pathogens that affect peanut, so peanut should not follow soybean. The sclerotia do not persist when buried deeper (6 inches) in the soil, thus deep plowing with a mouldboard plow can be a good management option. Some cultivars are less susceptible than others, but do not rely on host plant resistance alone for disease management. Fungicides are effectively used to manage this disease, which are applied preventively beginning approximately 60 days after planting or when canopy covers the furrow or early July, when the disease is often first observed in Arkansas.

Rhizoctonia foliar blight also known as “Rhizoctonia aerial blight” was first reported in 2013 in Arkansas. Though 10% defoliation of the leaves in the lower canopy has been observed in localized areas of the field, yield loss are negligible.

Foliar symptoms are often observed after canopy closure on leaves within the lower 1/3 of the plant canopy. Leaf lesions first appear as water-soaked, gray-green lesions that later become tan to brown (Fig. 1). Similar symptoms develop on the leaf petiole, but very rarely affect stem tissue even in severe cases of defoliation. Leaves are often matted together with long stands of “cat-hair-like” hyphae that extended along stems, petioles and newly affected leaves (Fig. 2). Dark brown spherical sclerotia (1-3 mm diam. or lead shot sizes from no. 9 (2 mm) to no. 4 (3 mm)) form on the surface of infected leaves and stems in the lower canopy. Environmental conditions that favors disease development is warm, wet, humid conditions.

Rhizoctonia foliar blight is caused by Rhizoctonia solani (AG 1-IA), which causes sheath blight of rice, banded sheath blight of corn and aerial blight of soybean. Fields with a history of aerial blight of soybean may be problematic for Rhizoctonia foliar blight of peanut. However, rotation that includes peanut and soybean should be spaced between several years of no legume crops. This disease is often more problematic in furrow-irrigated than overhead irrigated fields. Furrow irrigated water moves sclerotia to the lower end of the field or in contact with peanut leaves as peanut limbs grow into the furrow late in the growing season. Fungicides that are effective on southern blight are also effective on this disease.

Figure 1. Water-soaked, gray-green lesions caused by Rhizoctonia foliar blight of peanut.

Figure 2. Cat-hair-like hyphae from Rhizoctonia solani AG 1-IA clinging to peanut limbs and on leaves in lower canopy.

Aspergillus crown rot is caused by Aserpgillus niger, which can be found in most peanut fields in Arkansas. The fungus causes seedling blight and most commonly observed before flowering. Infected plants often wilt next to healthy plants. Wilted plants often have a ring of black spores near the soil line (Fig. 1), which is a sign that the pathogen that caused the wilt it A. niger. The fungus is active when soil temperatures are warm and drought-stressed plants are predisposed to be more susceptible to infection. Crown rot is primarily a seedling disease, but infections can be observed in older plants. Overall, crown rot is of minor importance in Arkansas as it causes little to no yield losses. However, with continued production and use of poor quality seed losses could be greater and thus yield limiting. Use of good quality seed, seed-applied fungicides, and planting in optimum growing conditions can mitigate this disease.

Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus (TSWV) is widely distributed in Arkansas and can cause 50% yield losses on very susceptible cultivars. Because most of the peanut cultivars grown have resistance to TSWV this is not a major issue.

Infected susceptible peanut plants exhibit characteristic ring spotting or mottled leaves (Fig. 1 & 2). Advanced symptoms include stunted plants that wilt and die. Tobacco thrips and western flower thrips are vectors for the virus. Thrips transmit the virus from TSWV infected plants to peanut plants. TSWV has a wide host range that includes many weed species.

The most economical and practical management practice is the use of host plant resistance. Many runner-type peanut cultivars grown in Arkansas are resistant to TSWV. Insecticides applied at planting, in-furrow like phorate (Thimet 20G) or imidacloprid can suppress thrips feeding, which has suppressed early season thrips infection in other peanut growing regions. Cultural practices include planting during optimum conditions to achieve uniform plant stands and planting higher plant populations have also been effective in minimizing the spread of TSWV in a field.

Figure 3. Ring spotting of peanut leaf by Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus.

Figure 4. Mottling of peanut leaves by Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus

Pod Rot is often caused by one or more fungal pathogens. Pathogen identification is important to deploy an accurate management strategy. Pythium pod rot is caused by Pythium spp., and characterized by greasy-appearing, brown to black lesion on a soft pod. Rhizoctonia pod rot is caused by Rhizoctonia solani and characterized by dry, brown to dark brown lesion on a firm pod (Fig. 1). The pathogens that cause southern blight and Sclerotinia blight cause pod rot, and are suppressed with fungicide use. Pod rot by Rhizoctonia and Pythium is often more problematic in furrow-irrigated than pivot-irrigated fields. Pod rots often increase slowly in severity and incidence over time so scouting fields after peanuts have been dug can be a good time to inspect for pod rots. Proper fertilization levels, especially calcium can suppress pod rots caused by Pythium. Crop rotation is somewhat effective, especially with grass crops, corn and grain sorghum, but both Rhizoctonia and Pythium have a wide host range that includes many of row crops grown in Arkansas. Fungicides only provide partial control and do not always increase yield. See MP 154 for current recommendations on fungicides used to manage pod rots.

Fig. 1. Pod rot symptoms caused by Rhizoctonia solani.

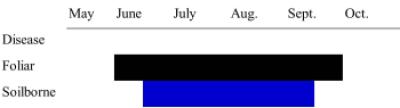

Though disease pressure is relatively low in Arkansas fungicides are applied proactively in a two or three block program depending on severity of soilborne diseases. Currently, soilborne diseases are the main issues, which are often managed with fungicides because resistance is lacking. It is important to apply the fungicide where infection is occurring, near the soil surface. In some cases a higher volume of water (20 gal water/A) is sufficiently, but more often additional water is needed. Applying a fungicide prior to a rain shower or use of overhead irrigation can distribute the fungicide into the lower canopy. Applying fungicides at night when tetrafoliate leaves are closed can also be beneficial and has been effective in other peanut producing regions. Some fungicides like tebuconazole and propiconazole have soilborne and foliar activity thus these fungicides can provide dual purpose for managing peanut diseases. See MP 154 for other fungicides with both soilborne and foliar disease efficacy. Below is a general timeline of when soilborne and foliar diseases are most likely a threat in peanut (Table 1).

Table 1. General timeline of soilborne and foliar diseases in peanut.