Commercial Horticulture

Assessing the Utility of Native Plant Species for Pollinators and Tree Fruit Orchards

Introduction

Graduate student Lilia Beattie standing in a native floral resource plot at the Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research & Education Center in Fayetteville, AR.

Wild bees and other nectar and pollen-feeding insects provide important pollination services in wild plant communities and in commercially-cultivated, pollinator-dependent, high-value crops.[1,2] A diversity of pollinator species provides higher rates of pollination and therefore, higher yields.[3] While bees are the most efficient pollinators, an assemblage that includes non-bees, such as; wasps, beetles, butterflies, moths, and flies, increases the overall pollination rates.[4] In addition to a global decline of insect pollinator abundance and diversity, colonies of managed honeybees have been declining due to multiple interactive factors, leading to higher costs to growers.[5] Domesticated bees cannot meet the demand as the market for pollinator-dependent crops grows worldwide.[6,7] Some growers have shifted to rely entirely on wild pollinators.[8] Because target crop species have a limited bloom time, in order to attract and retain an abundance and diversity of pollinators, there must be ample floral and nesting resources throughout the foraging season and within a limited flight range.[9,10] Therefore, growers are benefiting from the conservation, restoration, and management of diverse native wildflower communities adjacent to, or within, the farming system.[11,12,13]

In order to design optimal floral resources, this study evaluates pollinator visitation rates to pollen and nectar-abundant native plant species by different categories of bees and flower-visiting insects. Most research being done on floral resource provisioning is taking place in Europe. Very few studies have been conducted in the United States. Even less attention has been given to non-bee pollinators.

Study Objective

The main objective of this study was to determine the visitation of bees and other flower-visiting insect pollinators to rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccafolium) and tall goldenrod (Salidago altissima).

In the summer and fall of 2021, data was collected on rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccafolium) and tall goldenrod (Salidago altissima) in a native floral resource plot on the Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research & Education Center in Fayetteville, AR. On rattlesnake master, pollinators were observed in 8 (0.5 m2) plots for 10 minutes, for a total of 144 observation sessions, or 1,440 minutes. On tall goldenrod, pollinators were observed in 3 (0.5 m2) plots for 15 minutes, for a total of 102 observation sessions, or 1,530 minutes. The number of flower visitations were recorded by each category of pollinator; honeybee, bumblebee, carpenter bee, green halictid bee, other solitary bees, fly, beetle, wasp, and Lepidoptera.

Results

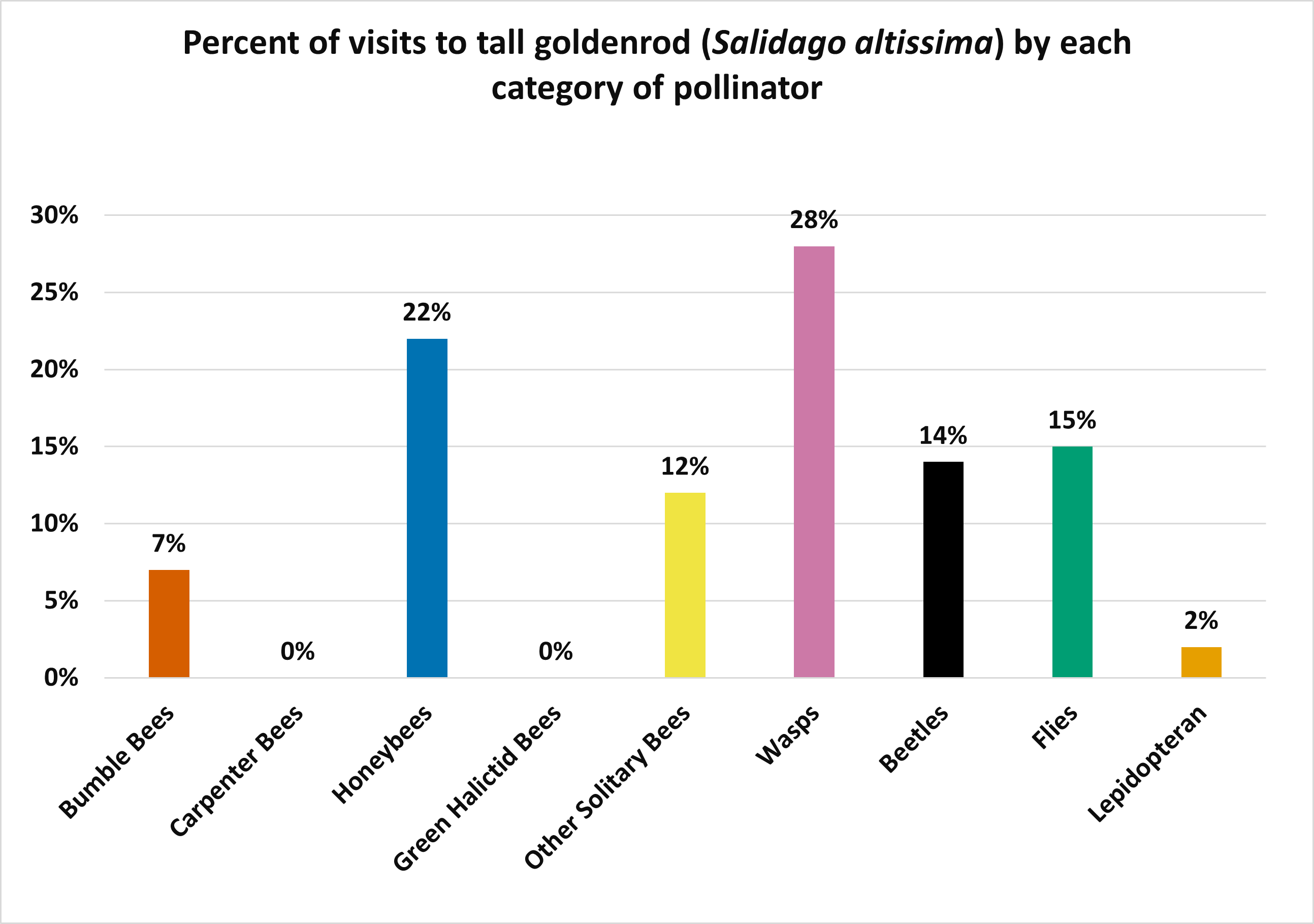

Figure 1: Percent of visits to tall goldenrod (Salidago altissima) by each category of pollinator: bumblebees, carpenter bees, honeybees, green halictid bees, other solitary bees, wasps, beetles, flies, and lepidopterans.

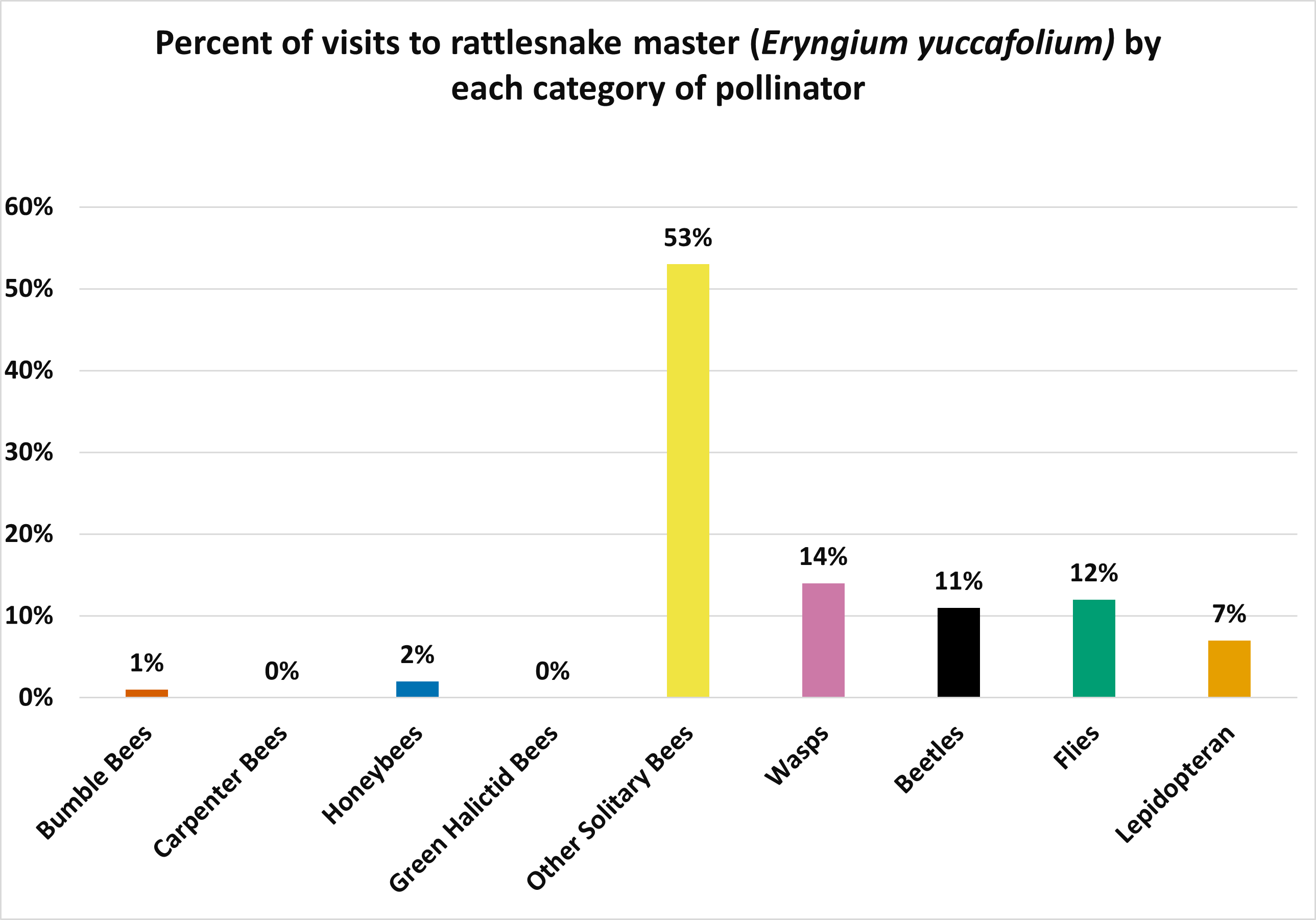

Figure 2: Percent of visits to rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccafolium) by each category of pollinator: bumblebees, carpenter bees, honeybees, green halictid bees, other solitary bees, wasps, beetles, flies, and lepidopterans.

Conclusion

Rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccafolium) was primarily visited by “other solitary bees”, which was almost exclusively very tiny sweat bees. Their visitation numbers accounted for 53% of all visitations across all pollinator categories. The gap between their numbers and those of other pollinator categories is highly significant.

Tall goldenrod (Salidago altissima) was primarily visited by wasps, but honeybees came in a close second, 28% and 22% respectively. Flies, beetles, sweat bees, and bumblebees were also very active on tall goldenrod, ranging from 7%-15%. Few of these four pollinator categories have significantly different visitation rates from each other.

While a few green halictid bees and carpenter bees were observed, their numbers were very low relative to the overall number of pollinator visitations. Future studies will assess the pollinator attractiveness of additional native plant species to maximize floral resources throughout the foraging season.

New SSARE Project

"Utility of Native Floral Plantings Between Tree Rows for Conservation and Management of Wild Bees and Other Beneficial Insects in Tree Fruit Orchards"

With this on-farm study, we aim to quantify the ecosystem services of wild bees and other beneficial insects that help in suppressing crop pest populations by biological control. Following the establishment of diverse native floral resource plots between rows of apple trees in NW Arkansas apple orchards, we will assess their effectiveness at attracting and retaining diverse assemblages of these beneficial insects. Specifically, we will measure the abundance and diversity of wild bees and syrphid flies over two seasons and their role in enhancing crop yield. We will also measure the community of other beneficial insects and their role in biocontrol.

In light of pollinator declines, conserving habitat and supporting populations of wild pollinators is an increasing concern among growers of pollinator-dependent crops. This project would be among the first to assess the effectiveness of providing these newly designed with-in orchard swaths of pollinator habitats and the findings of this study would be helpful to the fruit growers’ community in this region.

References

- Ollerton, J., Winfree, R., and T. Tarrant (2011). How many flowering plants are pollinated by animals? Oikos 120, 321–326.

- Potts, S.G., Imperatiz-Fonseca, V., Ngo, H.T., Aizen, M.A., Biesmeijer, J.C., Breeze, T.D., Dicks, L.V., Garibaldi, L.A., Hill, R., Settele, J., and A.J. Vanbergen. (2016). Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being. Nature 540, 220–229.

- Martins, K.T., Gonzalez, A., and M. J. Lechowicz (2015). Pollination services are mediated by bee functional diversity and landscape context. Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment. 200: 12–20.

- Rader, R., Bartomeus, I., Garibaldi, L.A., Garratt, M.P.D., Howlett, B.G., Winfree, R., and A. Cunningham (2016). Non-bee insects are important contributors to global crop pollination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (1); 146-151.

- Stokstad, E. (2007). The case of the empty hives. Science, 316 (5827). 970-972.

- Aizen, M.A., and L.D. Harder (2009). The global stock of domesticated honey bees is growing slower than agricultural demand for pollination. Current Biology 19(11): 915–18.

- Klein, A.M., Vaissière, B.E., Cane, J.H., Steffan-Dewenter, I., Cunningham, S.A., Kremen, C., and T. Tscharntke. (2007). Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences. 274, 303–313.

- Kremen, C., Williams, N.M., Bugg, R.L., Fay, J.P., and R.W. Thorp (2004). The area requirements of an ecosystem service: Crop pollination by native bee communities in California. Ecology Letters 7: 1109–1119.

- Sidhu, C.S. and Joshi, N.K. (2016) Establishing Wildflower Pollinator Habitats in Agricultural Farmland to Provide Multiple Ecosystem Services. Front. Plant Sci. 7:363.

- Heller, S., Joshi, N.K., Leslie, T., Rajotte, E.G., and D.J. Biddinger (2019). Diversified floral resource plantings support bee communities after apple bloom in commercial orchards. Scientific Reports.

- Garibaldi, L.A., Steffan-Dewenter, I., Winfree, R., Aizen, M.A., Bommarco, R., Cunningham, S.A., Kremen, C., and L.G. Carvalheir (2013). Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 339:1608–11.

- Fuccillo Battle, K., de Rivera, C.E., and M.B. Cruzan (2021). The role of functional diversity and facilitation in small-scale pollinator habitat. Ecological Applications. 31(6).

- Kammerer, M.A., Biddinger, D. J., Rajotte, E. G., and D. A. Mortensen (2016a). Local Plant Diversity Across Multiple Habitats Supports a Diverse Wild Bee Community in Pennsylvania Apple Orchards. Environmental Entomology 45(1), 32-38.