Parasites in Small Ruminants

One of the biggest health problems faced by small ruminant producers in the southeast

and south central U.S. is internal parasites. Internal parasite management, especially

of Haemonchus contortus (barber pole worm), is a primary concern for the majority

of sheep and goat producers. These parasites have become more difficult to manage because of developed resistance

to nearly all available dewormers.

We have all become accustomed to having several highly effective drugs to select from

for the treatment of worms, but as the level of parasite drug resistance increases,

these drugs are not the easy solution they once were. Drug resistant worms are spreading

and new products are not available. As a result, producers must begin thinking more

creatively about how to effectively control worms in their animals. No longer can

we recommend control programs based on drug treatment alone that will be satisfactory

for most producers. Producers must design an integrated parasite control program because

the numbers of worms, their impact on your herd and their level of resistance to drugs

will vary from farm to farm.

What are the most important worms to be aware of for small ruminants?

The most important worm parasites are the gastrointestinal trichostrongyles. This

is a whole family of worms, but the really important one is the barber pole worm (Haemonchus contortus) -- it causes many small ruminant deaths every year. This is

a bloodsucking parasite that causes anemia but usually not scouring. Some other near

relatives of the barber pole worm can cause scouring, but are not the annual cause

of disease and death like barber pole worm.

In order to use anthelmintics (dewormers) and other means of parasite control most

effectively, there are some facts about the life cycle, which are important to understand.

Adult female worms produce eggs that are passed in manure. Larvae hatch out and go

through several stages of development in the environment before they can infect the

next host. During the warm months of the year, enormous numbers of larvae can build

up on your pasture.

Virtually all these worms need grass for successful development; they do not successfully

develop on dirt.

The success of larvae outside the host depends on the climate. Moisture and warmth

(50 degrees F and above) are necessary for development and survival. Dry weather is

very hard on these larvae once they are out on the grass.

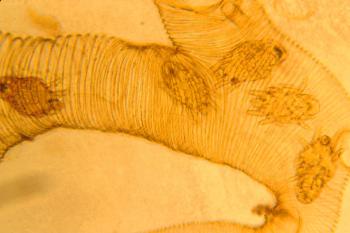

Drawing of a blood vessel with several parasites inside it. The blood vessel is gold

in color with the parasite bodies tinged in red so they are more easily seen. (Image

courtesy of USDA.)

Haemonchus larvae can also undergo a process called ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT where they

sit quietly in the stomach following infection and don't become adults until several

months later. This is an important adaptation for keeping the worm around through

cold winters when eggs and larvae don't survive well on pasture.

The worms that became arrested in the fall resume development in the spring and reproduce.

This information can be used in several ways to target parasite control for times

of the year when it will have the greatest impact.

Worms are a part of the natural sheep and goat world. We cannot eradicate them as

long as sheep and goats are on pasture. The goal is to maintain the parasites at a

level that will not produce any illness or economic loss.

Because the problem of drug resistance is steadily increasing it is important for

each producer to look at his/her management system as a whole and find things beside

drugs that will help control parasites and create a holistic management program. Remember,

anytime we rely on a single product or method of control the worms will eventually

adapt and outwit us.

If you include some of the following techniques, the need for frequent deworming treatments

should be reduced.

-

-

- Check Your Animals: With some parasites, like coccidia, signs of scouring will alert you to a problem.

With barber pole worm there is no scouring but there is anemia with pale mucous membranes.

Get into the habit of checking the color of the membranes around the eye (FAMACHA

scoring)-this is the easiest place to see anemia and will alert you when a problem

is developing.

- Don't Pinch Pennies on Diet: Many experiments over the years have shown that animals on a high nutritional plane

are more resilient to the adverse effects of parasites than those on marginal diets.

Protein and minerals, as well as energy, are important in resisting the effects of

barber pole worm because new red blood cells must be generated to replace those lost

to the parasites. Nutrients are also needed to develop an immune response to the parasites.

- Appreciate Normal Immune Responses to Parasites: Animals will develop some immunity against worm parasites, If we list categories

of animals from least to most immune it would generally be: a) Kids and lambs (require

a full grazing season to develop immunity), b) pregnant and lactating does/ewes, c)

Bucks and d) Dry does/ewes.

- Concentrate your worm control efforts on the animals that need it the most and remember that immunity will be overcome if sheep and goats are exposed to high

numbers of worm larvae.

- Consider resistance to parasites in your selection program. There is definitely a genetic component in resistance to parasites that is most likely

related to the immune response. If you have animals that get anemic before the others,

consider culling them. Similarly, keep the ones that never seem to get anemic.

- Use Drugs Wisely: All of the available chemical dewormers fall into 3 major classes of dewormers.

You need to recognize which ones are in each class because once worms become resistant

to one drug in a class, they will be resistant to the other drugs of that class. Drugs

that are not FDA approved for use in sheep and/or goats can only be used following

consultation with your veterinarian. Use the Correct Dose - Under dosing promotes

the development of resistance.

- Don't Bring Resistance to Your Farm: If you get new animals, do not let them bring in worms with drug resistance. Quarantine

new animals before co-mingling them with your existing herd.

For more information contact:

Dr. Dan Quadros

Asst. Professor - Small Ruminants

Phone: 501-425-4657

Fax: 501-671-2185

Email: dquadros@uada.edu

Office:

University of Arkansas System

Division of Agriculture

Cooperative Extension Service

2301 S. University Ave.

Little Rock, AR 72204

Sign up for our E-Newsletter