The History of Extension

C.E.S.P. 9-9: History

Supersedes: 4-5-02

The University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service History

Summary: Beginning of Extension Work in the United States

What is now Cooperative Extension work in the United States came into existence prior to 1850 when agricultural societies in many Eastern states were instrumental in providing public lectures on agricultural topics. Farmers' Institutes were held in some states as early as 1863. By 1899, at least 47 states and territories were holding such institutes, using staff members of agricultural colleges and successful farmers as speakers.

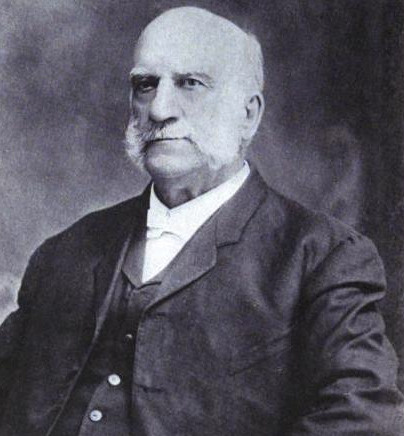

Even though Extension-type work was being carried out in the 1850's, prior to his entry into the field of agriculture, Dr. Seaman A. Knapp is considered to be the founder of the Extension Service. A brief history of the Extension Service which was taken from "Recollections of Extension's History," by J. A. Evans, administrative assistant, Georgia Agricultural Extension Service, University of Georgia, follows.

"Someone has said that all great organizations and institutions are but the lengthened shadow of a man and an idea."

That is certainly true of the Cooperative Extension Service. The man was Dr. Seaman A. Knapp; the idea, that of teaching by demonstration. This idea was not a sudden inspiration; it was developed by trial and error over a period of years.

What was the role of Dr. Knapp in Extension?

Dr. Knapp was born in the state of New York on December 16, 1833, and was educated there, married, and settled down to teaching. To found a great college was his dream. He became ill, and on his physician's advice moved to Iowa in 1866, where he settled down on a small farm. However, farming proved to be too strenuous for him. He moved to a nearby town and was later appointed superintendent of the State Asylum for the Blind located there. He served in this position efficiently for several years, although for a large part of the time he was confined to a wheelchair. Later, he was appointed professor of agriculture at the Iowa State College of Agriculture in Ames, Iowa.He later became president of that institution.

In 1896, he resigned as president of the college to go to Louisiana as manager of a company which planned to colonize a million or more acres of land it owned in that state. Again, the whole course of his life was changed. It was very expensive to bring immigrants to Louisiana; but the company advertised extensively throughout the West and North, and home seekers were brought there by the trainload. For some reason, they wouldn't buy the land.

The natives of the area, who made their living by grazing inferior cattle, believed that the land was not fertile enough for farming. When prospective settlers talked with them, they expressed this belief. Years later, Dr. Knapp, in relating this experience said, "In desperation, we then resorted to demonstrations." He subsidized a few good farmers from the Middle West, placing one in each township; after two or three years they were able to prove that the soil was productive. He then experienced no difficulty in settling that great area with middle-western and northern people, and it became a rich and prosperous agricultural section. He said, "I then learned the philosophy and power of agricultural demonstrations."

Dr. Knapp believed that rice would be the best cash crop for the area.

But the varieties then grown broke up too much in milling and were not, therefore, commercially satisfactory. After some discussion, Dr. Knapp was sent by Secretary Wilson, his old Iowa friend and associate, to China, Japan, and India to try to find better varieties of rice. He discovered and introduced one or two new varieties that became very popular and insured the success of rice as a commercial crop in that section.

Shortly afterwards, Dr. Knapp was given a permanent position in the Bureau of Plant Industry of the United States Department of Agriculture. At that time, this Bureau was especially interested in securing the adoption of better farming practices in the South and in finding a way to get the results of research to farmers in such a way that they would readily accept better farming practices and put them into use on their own farms. Bulletins, short courses, and other methods then in use had not proven effective. Dr. Knapp suggested demonstration farms. Accordingly, in 1902 the Bureau started two distinct lines of demonstration work in the South.

Dr. Knapp was in charge of "demonstration farms"

Demonstration farms were designed to show how to increase yields of the standard crops. Dr. Spillman was in charge of "diversification farms" which were designed to teach the value of possible new cash crops for the South, especially truck crops. Both were government farms conducted by paid managers. Dr. Knapp was not satisfied that the "demonstration farms" would serve the purpose intended. They had served him well when the purpose was only to prove that the soils of the coastal plains of Louisiana were fertile, but the objective now was to teach new methods of producing standard crops. Farmers, he thought, would discount results obtained on such farms and say, "We could do that too if we had the government backing us." He conceived the idea of demonstration farms, established by the community itself, and conducted without government subsidy.

While in New York early in 1903, Dr. Knapp met E. H. R. Green of Terrell, Texas, president of the Texas-Midland Railway. Mr. Green became very much interested in Dr. Knapp and his idea of "community demonstration farms." When he returned to his home, he told the chamber of commerce about Dr. Knapp and his plan and suggested that he be invited to Terrell to explain it. This was done. Dr. Knapp accepted the invitation, and the Porter Community Demonstration Farm resulted from that meeting. The businessmen of Terrell raised $900 to guarantee the demonstrator against loss, and Walter C. Porter, a farmer near Terrell, agreed to farm about 70 acres of his land according to Dr. Knapp's instructions and keep records of costs, yields, and receipts.

Best practices meant more profits.

At the end of the year, Porter reported that he made $700 more by farming according to Dr. Knapp's instructions than he would have made had he followed his former practices. In much Extension literature, it is said that this incident was the beginning of the Farmers' Cooperative Demonstration Work and that the purpose of the farm was to show that cotton could be grown in spite of the boll weevil. This is not correct. Weevil infestation had not reached this part of Texas in 1903, and the farm had no relation whatever to the weevil control campaign begun the following year. The Porter farm is historically important, however, because it was a laboratory in which Dr. Knapp tested the teaching value of his idea of community demonstrations, which later did become the basis of the Farmers' Cooperative Demonstration Work.

By 1903 the boll weevil, which invaded the state from Mexico some years before, had spread across much of the southern half of Texas, bringing ruin to both farmers and businessmen in all the infested areas. At a great mass meeting in Dallas, Texas, early that fall which was attended by the Secretary of Agriculture, Texas congressmen, businessmen, and farmers, it was decided to urge the Congress to appropriate $500,000 to help fight the weevil. From this meeting, the Secretary of Agriculture, the chief of the Bureau of Plant Industry, and other Department of Agriculture officials went with Dr. Knapp to inspect the community demonstration farms at Terrell, Texas. The Secretary and other officials were then convinced that the idea could be used in the boll weevil fight, if the federal appropriation was made. Late that fall Congress did appropriate $250,000 for this purpose.

It was not until January 15, 1904, that President Roosevelt approved the bill and the money became available.

While the appropriation was pending, the Secretary and heads of departments had been planning how the money could best be used and were ready to start immediately. The appropriation was made to the Secretary to be used at his discretion. One-half was allotted to the Bureau of Entomology and one-half to the Bureau of Plant Industry. Dr. Knapp received $27,000 of the B. P. I. allotment to launch farmers' cooperative demonstrations designed to prove that farmers could still continue to grow cotton in spite of the boll weevil.

Dr. Knapp opened an office in Houston, Texas, on January 25.

He chose Professor G. W. Curtis of Iowa, an old friend and associate, as his assistant. A few civil service clerks from the B. P. I. also joined him.

His first act was to call a conference on January 27, 1904, of the agricultural and industrial agents of the various railway systems in Texas. At this conference, it was decided that a small force of field men would be necessary. The appointment of Mr. W. M. Bamberg as the first "special agent" is dated on that day. The railway representatives were asked to recommend other men located on their respective railway lines for similar positions.

Within the next few weeks, some 25 or 30 more "special agents" of the B. P. I. were appointed. Among them were W. C. Proctor, W. D. Bentley, J. L. Quicksaul, and J. A. Evans. Mr. Proctor and Dr. Evans were appointed on February 12, 1904, Mr. Bentley and Mr. Quicksaul about a week later. Because of their long connection with the work, they came to be called "The Big Four" in the early years of the work. Proctor and Bentley died in service, the first as director of Extension in Texas and the second as assistant director of Extension in Oklahoma. Quicksaul became state agent for West Texas and later district agent after the Smith-Lever Bill was passed, resigning this position only a few years before his death.

The first appointments were of an emergency nature and, with one or two exceptions, for 60 days only. The pay was $60 per month and actual travel expenses. For the most part, the men were farmers or had considerable farm experience; they ranged in age from 30 to 50 years. So far as it is known, none had any agricultural college training.

Their job was to get small community cotton demonstration farms, from five to twenty acres each, established near the principal towns in each county and to enroll as many other farmers as possible as cooperators. Planting seed and fertilizer sufficient for the demonstration farms were furnished the demonstrators, but not their cooperators. Both demonstrators and cooperators agreed in writing to follow the instructions of Dr. Knapp as to preparation, cultivation, etc., of the demonstration and to make a report of yields and costs at the end of the season. A cooperator might plant as little as one acre. Agents were expected to visit the demonstrators at frequent intervals to give instructions but were not expected to visit cooperators. They received instructions by mail and were also supposed to observe the methods used on the nearest demonstration farm.

In "Recollections of Extension History," J. A. Evans discusses his assignment as a special agent.

"Two days after my appointment I started out. Livingston, Texas, was the first town at which I stopped. I didn't know a soul in the town, or any town or county in my territory for that matter. I inquired of the first intelligent-looking man I met, 'Who is the most progressive man in this town?' After asking several men this question I proceeded to hunt up the person who had been named oftenest. To him I explained my mission and asked him to get the businessmen together within the next hour at some convenient place so that I could explain the plan and put the proposal to establish a demonstration farm in that community before them. Without fail, by one means or another, we got a group of businessmen together, I explained my mission, and succeeded in getting anywhere from $50.00 to $150.00 subscribed to purchase seed and fertilizer for a demonstration farm or farms in every town where I stopped. A committee was named to complete the details of selecting a location and the demonstrator within 2 to 4 hours after landing in the town. Usually these details were also completed in that time.

The instructions given demonstrators and cooperators were very simple. They included the making of a good seedbed; using good seed of an early maturing variety; directions for the use of fertilizer; early planting; and intensive shallow cultivation. Perhaps one of the biggest changes we made in farm practices of the early days was in the methods used in the cultivation of cotton and corn. The farmers of the South had up to that time usually used deep cultivation with one-horse turning plows, especially in 'laying by' the crop. I remember in one county in Arkansas where we used a simple one-horse implement, called a 'Gee Whiz' in cultivating the demonstration farms. It was entirely new in that area.

One hardware man in the county sold two carloads of the implements the next year. As a direct method of weevil control, we advocated picking the early emerging weevil, if numerous, out of the bud of the young cotton stalks before 'squares' began to form, and the picking up and destroying of the weevil-infested squares later. To show how heavy the early infestation of the weevil was, in some years I have known demonstrators in Louisiana to pick 5,000 or more adult weevils per acre from the cotton buds, before the squares appeared. These methods proved effective when carefully followed."

Timeline of Extension's early days

- About 7,000 demonstrators and cooperators were enrolled in 1904. The yields of cotton on the demonstration farms and reported by cooperators were, as a rule, at least twice as large as the average yields on farms in the same localities where the demonstration instructions were not followed.

- Work was carried on in the same way in 1905. An agent was appointed in Arkansas and Mississippi, and the number in Texas and Louisiana was increased. Dr. Knapp's assistant, G. W. Curtis, entered private business, and in March, 1905, J. A. Evans succeeded him.

- The first county agent was W. C. Stallings. Local businessmen and farmers petitioned Dr. Knapp to assign a man to work exclusively in Smith County, Texas. He agreed to do so if they would pay at least half of the agent's salary. This was arranged, and Stallings was selected as the agent. His appointment was dated November 12, 1906.

- The example set by Smith County, Texas, was soon followed in other counties. Before the beginning of the crop season of 1907, five Texas counties and two Louisiana parishes had county agents, with businessmen and farmers cooperating and paying the salaries.

- A definite field organization for each state was set up with a state agent, district agents, and county agents. Mr. Evans was made state agent for Louisiana and Arkansas, with headquarters at Shreveport, Louisiana. Texas had two state agents--W. C. Proctor in East Texas and J. L. Quicksaul in West Texas. W. D. Bentley was state agent for Oklahoma. R. S. Wilson became state agent for Mississippi and Alabama.

Boys' Corn Clubs and Girls' Tomato Clubs - early years of 4-H

In 1907, W. H. Smith, a county superintendent of schools in Holmes County, Mississippi, started Boys' Corn Clubs in the schools of that county to grow corn as a demonstration, much as some of their fathers were growing cotton. Dr. Knapp was interested and had him appointed as a "collaborator" in the Department of Agriculture to give him the franking privilege to aid in carrying on the work. The following year, clubs were started in two other counties in that state. Boys' Corn Clubs were made a definite phase of the demonstration work in 1909.

Early in 1910, Marie Cromer, a rural school teacher in South Carolina, was inspired by the stories of boys' club work and organized a Tomato Club for the girls of her school. "Once more Dr. Knapp seized upon an idea, and in vision saw it encompassing the entire South." He sent Mr. Martin to assist Miss Cromer with the canning work, and they made plans to promote such clubs as part of the demonstration plan.

Miss Ella Agnew also began some work in Virginia with girls comparable to the work being done in boys' clubs. Miss Agnew was appointed home demonstration agent on June 3, 1910, to work in three counties in Virginia; and Miss Cromer received a similar appointment to work in two counties in South Carolina on August 16, 1910. The girls' Tomato Clubs were thus formally launched as part of the demonstration work.

In the October report of that year to the General Education Board, Dr. Knapp said:

"The demonstration work has proven that it is possible to reform by simple means the economic life and the personality of the farmer on his farm."

The boys' Corn Clubs have likewise shown how to turn the attention of the boy toward the farm. There remains the home itself--and its women and girls. This problem cannot be approached directly. With these facts in view, I have begun a work among girls to teach one simple straight forward lesson which will open their eyes to the possibilities of adding to the family income through simple work in and about the home. The entire expense of the girls' Canning Club work in all states was at all times borne by the General Education Board. The initial appropriation for this specific work was $5,000 in 1911 and $25,000 in 1912. This indicates the immediate interest in and rapid growth of this phase of the work.

Dr. Knapp regarded working with the girls as the best way to reach their mothers. This was his ultimate goal; it would complete the demonstration plan.

Dr. Knapp died April 1, 1911. He was buried with simple but impressive honors on the campus of the agricultural college at Ames, Iowa, where he once served as president.

In the last seven years of his life, he initiated and progressively expanded an educational movement that attracted the attention of the entire world and which he predicted, "Tis destined ultimately to be adopted as part of the educational system of every civilized nation."

The underlying objective of all phases of the demonstration work, adult or youth, was to increase the earning capacity and the incomes of farm families--not as an end in itself, but as a means.

To Dr. Knapp greater earning capacity meant little unless translated into better schools, improved homes, better social and living conditions, and better people. It was not enough, he said, to have as an objective "We will increase the wealth and give the people earning power." We must also "try to turn all avenues of the wealth that we create into the proper channels, so as to create a better people." Increased yields per acre and per man by the intelligent use of more horsepower, improved machinery, and better farm practices, coupled with thrift and frugality, were the means he advocated for increasing incomes.

The Smith-Lever Bill was prepared and introduced simultaneously in both the House and Senate on September 16, 1913.

This bill was finally passed and approved by President Wilson, May 8, 1914. The Smith-Lever Bill authorized an appropriation of $9,100,000 to be allotted to the states for Cooperative Extension work in agriculture and home economics, payable over a period of nine years. An initial $10,000 payment was made to each state; the remaining allotments were to be offset by funds appropriated by the legislatures of the states "or provided by the state, county, college, or local authorities or individual contributions from within the state." This language was intended to make it impossible in the future for the work to be supported by organizations or wealthy individuals as in the instance of the General Education Boards in the South or the Council of Grain and Exchange in the Middle West.

The speeches in the House and the Senate in support of the Smith-Lever Bill and the wording of the bill showed conclusively that it was modeled on the work in the South and on Dr. Knapp's philosophy of demonstration teaching. In fact, one or more of the advocates said that the bill was designed to extend the Farmers' Cooperative Demonstration Work throughout the rest of the nation.

When the Smith-Lever Act became effective on July 1, 1914, the Farmers' Cooperative Demonstration Work was being carried on in 15 states. There were 1,151 employees; 279 of these were home demonstration agents and 53 were Black men and women agents. In 20 other states, the Office of Farm Management had perfected cooperative arrangements with the agricultural colleges, and 113 county agents were employed.

In the regular Department of Agriculture appropriation act for 1914, Congress gave the Secretary of Agriculture authority to prepare a plan for reorganizing that department. In March, 1914, plans to create a States Relation Service which was to have general supervision of the department's business relating to agricultural colleges and experiment stations and to put Dr. A. C. True, then director of the Office of Experiment Stations, as its head were announced.

This would include, of course, the administration of the Smith-Lever Act. Pending congressional authorization of the reorganization plan, a States Relation Committee was set up to handle these matters. This committee consisted of Dr. True and Dr. Allen of the Office of Experiment Stations and C. B. Smith, chief of the section of Farm Management demonstrations, and Bradford Knapp, chief of the Office of Farmers' Cooperative Demonstrations. The committee was responsible directly to the Secretary.

It was evident that many questions of policy and of the respective functions and powers of the Department of Agriculture and the colleges would arise in the conduct of Extension work under the Smith-Lever Act. Soon after its passage, therefore, a proposed memorandum of understanding covering policies and procedures between the Secretary of Agriculture and the land grant colleges, was drawn up and approved by the Secretary and the executive committee of the land grant colleges. This was submitted to the land grant colleges, and within the year all except those in two states had signed. This memorandum is still the basis on which the Extension work of the Department of Agriculture and the colleges is conducted.

The memorandum provided that each college would organize and maintain a definite and distinct administrative division for the management and conduct of Extension work in agriculture and home economics with a responsible leader selected by the college and acceptable to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and that all Extension funds received from state, federal, and other sources would be administered through such division.

The old office of "Farmers' Cooperative Demonstration" now became the Office of Cooperative Extension Work (South), and the Farm Management Demonstration Work became the Office of Cooperative Extension Work (North and West), both under the States Relation Committee.1

Beginning of Extension Work in Arkansas

About the earliest recorded historical fact pertaining to Extension work in Arkansas is the establishment of the Arkansas Industrial University (the land grant college) in 1872, founded in accordance with the Morrill (federal) Act of 1862. In 1875, the Arkansas General Assembly authorized the holding of agricultural and mechanical fairs. The Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station under the Hatch (federal) Act became active in 1888. A year later, the General Assembly created the Bureau of Mines, Manufacture, and Agriculture, with a commissioner in charge whose duties were primarily regulatory. However, he was expected to encourage and promote interest in other agricultural work and, especially, to keep an exhibit at his office in the state capitol building.

The first Cooperative Extension work conducted by the University of Arkansas was in 1905 when several Farmers' Institutes were held, but this work was limited because of a small state appropriation. Later the number of institutes held was increased as larger appropriations were made. These were discontinued after the Smith-Lever Act went into effect in 1914.

The Farmers' Cooperative Demonstrative Work of the United States Department of Agriculture under Dr. Knapp's direction was begun in Arkansas in 1905 with the appointment of J. A. Evans as state agent and A. V. Swatty as district agent. By 1907, four district agents and seven county agents had been appointed.

4-H Club work was started in 1909 and home demonstration (canning clubs) work was begun in 1911. The first Black county agent was appointed in 1914.

When the Smith-Lever Act went into effect, the personnel of the state organization (Farmers' Cooperative Demonstration Work) consisted of a state agent in charge, a state home demonstration agent, a state 4-H Club agent, three district men agents, several specialists, fifty-two county agents, fifteen home demonstration agents, and the necessary clerical force.

J. A. Evans, Recollections of Extension History, Extension Circular No. 224 (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service, 1938). pp. 1-51.